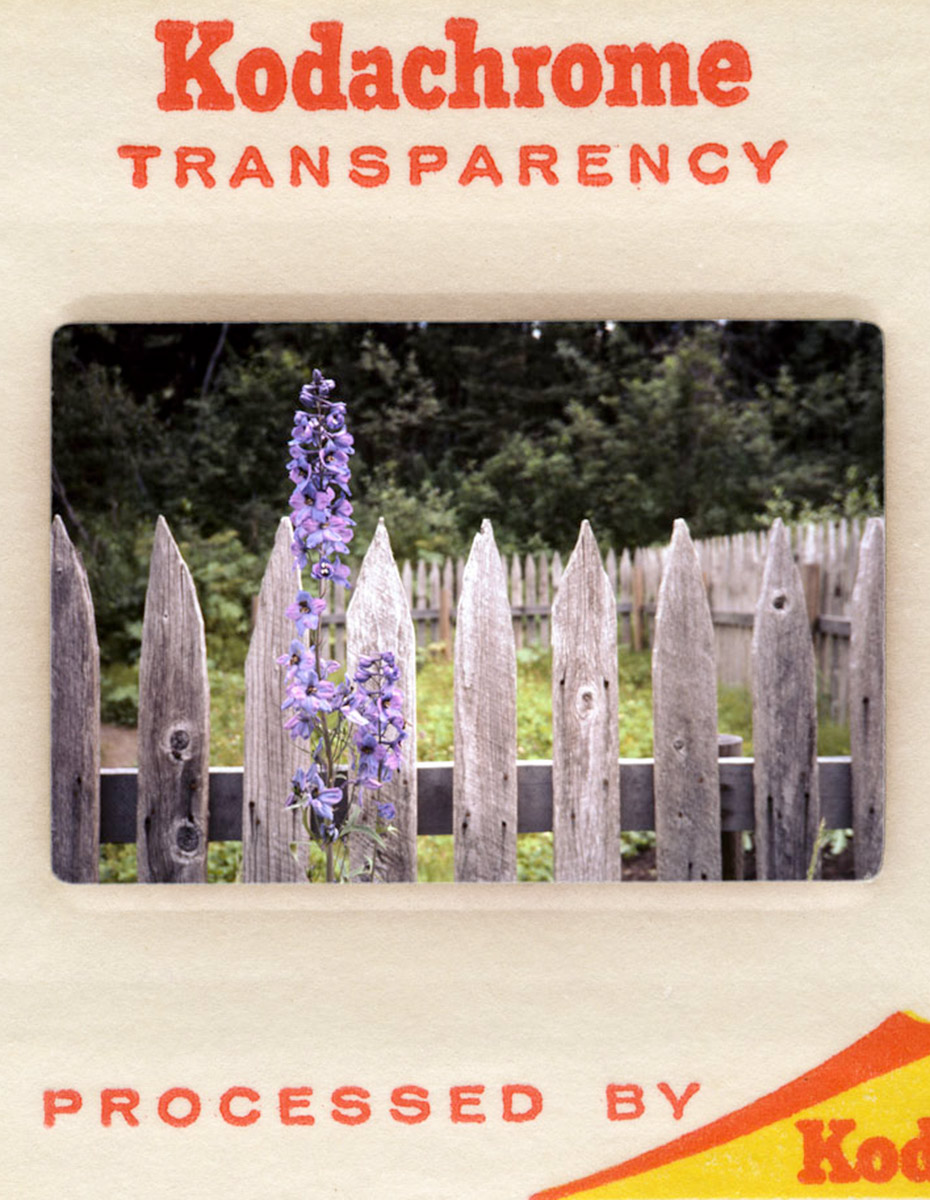

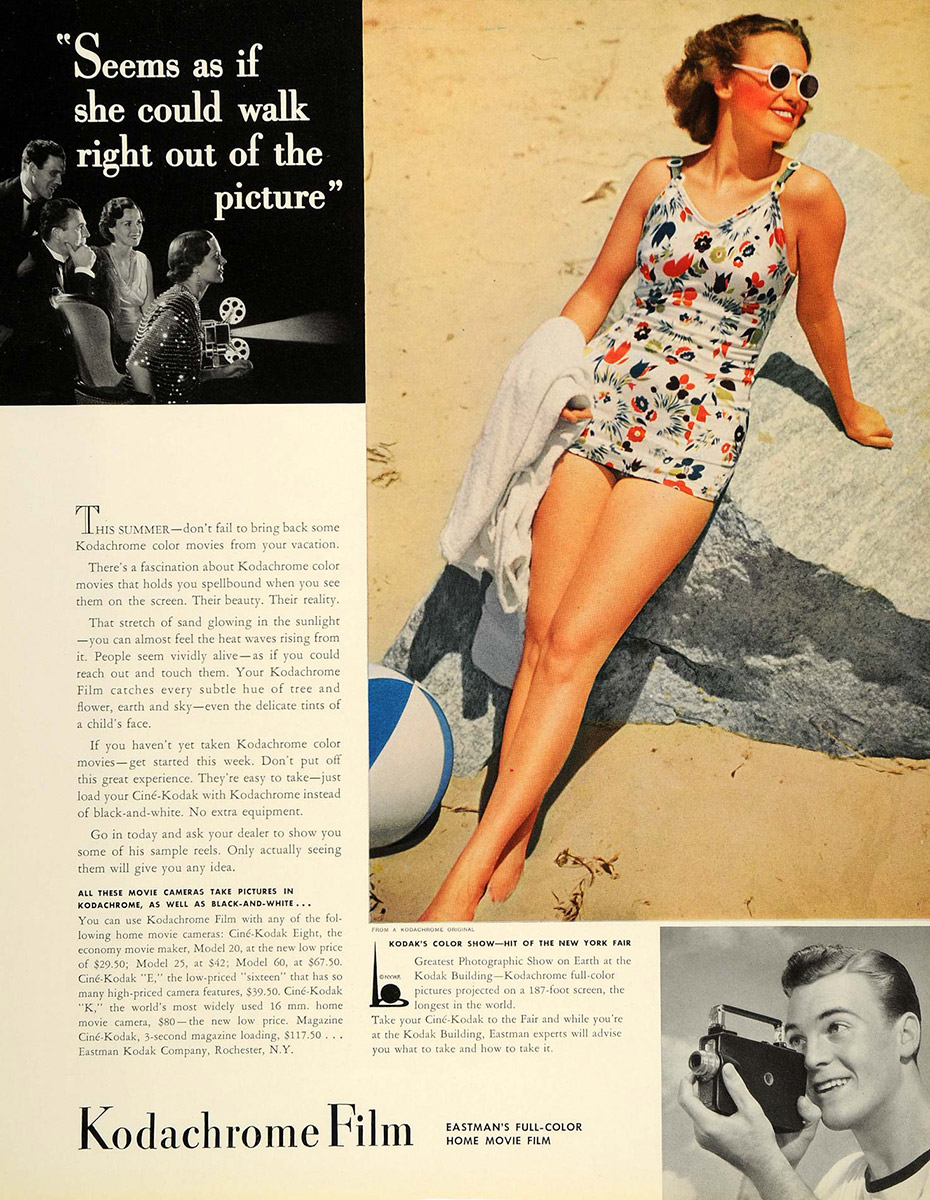

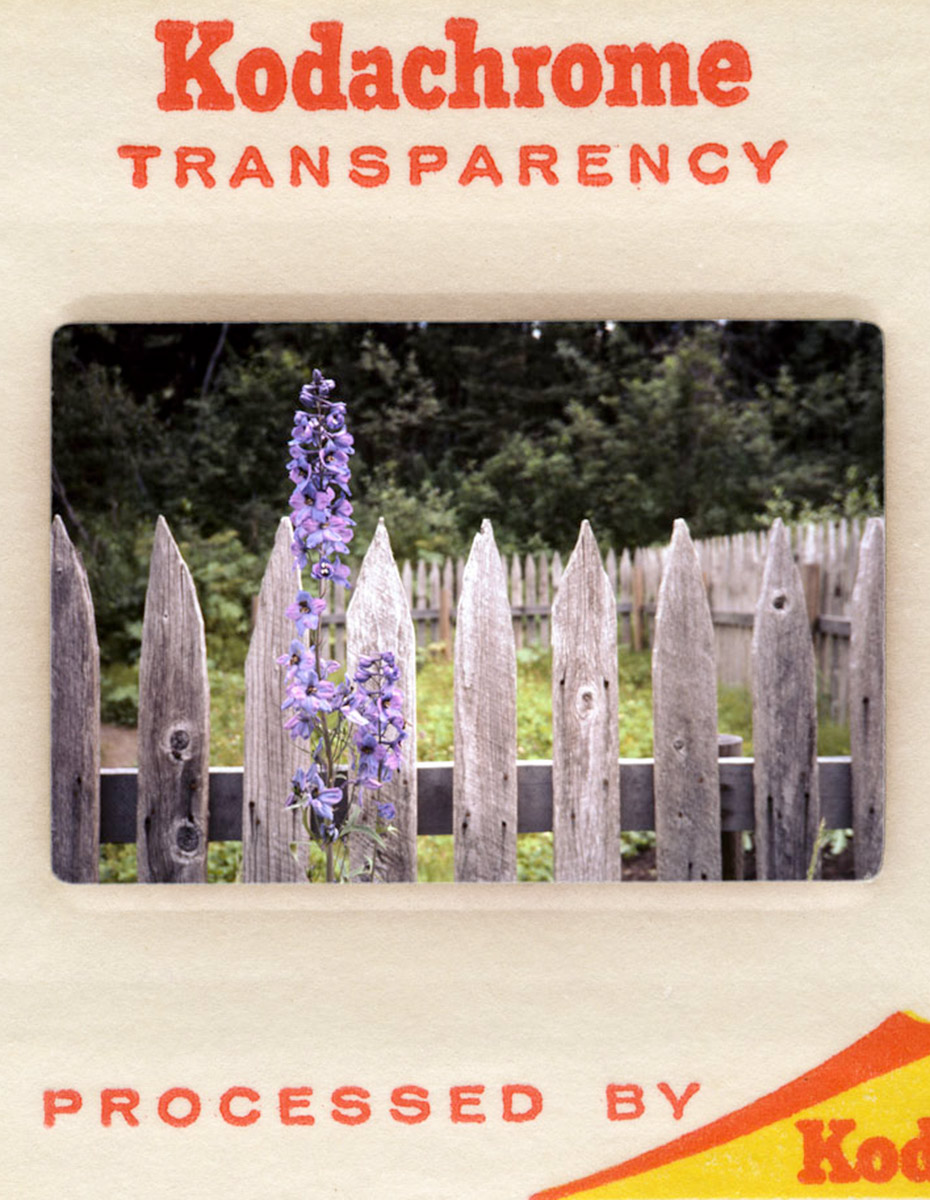

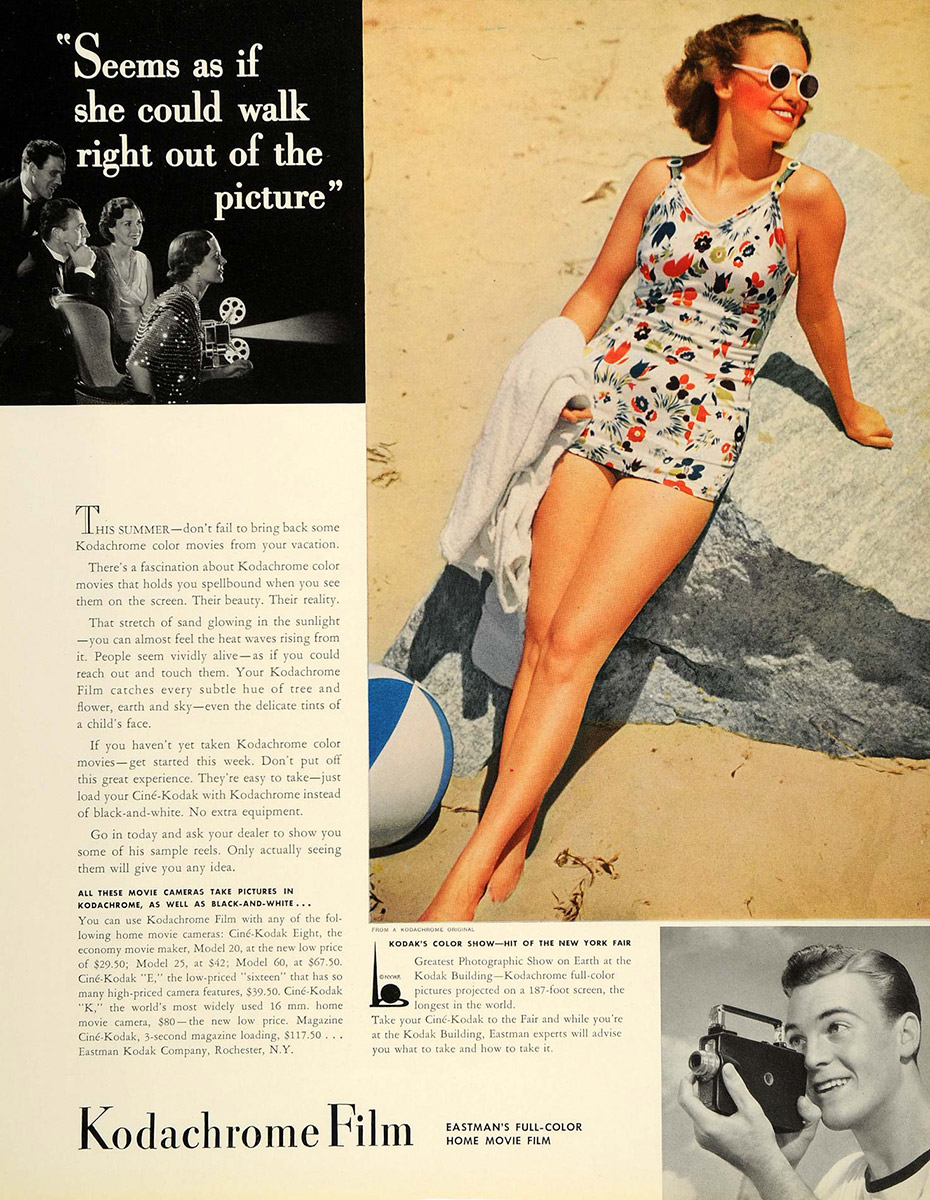

It wasn’t easy being green. Or yellow or red or blue, for that matter. While color photography had been around in one form or another since the 1860s, until the Eastman Kodak Company came out with its Kodachrome film in 1935, those wishing to capture a color image had to deal with heavy glass plates, tripods, long exposures and an exacting development procedure, all of which resulted in less than satisfactory pictures — dull, tinted images that were far from true to life. So while Kodak’s discontinuation of the iconic color film will affect only the most devoted photo buffs — sales of Kodachrome account for less than 1% of the company’s revenue — the June 22 announcement breaks one of the largest remaining ties to the era of pre-digital photography. It also ends a legacy that includes some of the most enduring images of 20th century America.

(See photos by Richard Avedon.)

The Kodachrome process — in which three emulsions, each sensitive to a primary color, are coated on a single film base — was the brainchild of Leopold Godowsky Jr. and Leopold Mannes, two musicians turned scientists who worked at Kodak’s research facility in Rochester, N.Y. Disappointed by the poor quality of a “color” movie they saw in 1916, the two Leopolds spent years perfecting their technique, which Kodak first utilized in 1935 in 16-mm movie film. The next year, they tried out the process on film for still cameras, although the procedure was not for the hobbyist: the earliest 35-mm Kodachrome went for $3.50 a roll, or about $54 in today’s dollars.

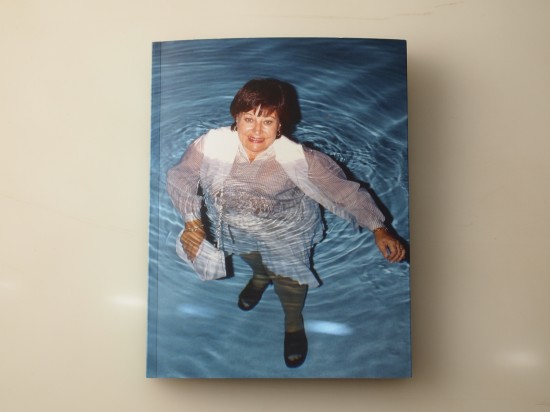

While all color films have dyes printed directly onto the film stock, Kodachrome’s dye isn’t added until the development process. “The film itself is basically black and white,” says Grant Steinle, vice president of operations at Dwayne’s Photo in Parsons, Kans., the only photo-processing center still equipped to develop Kodachrome film. Steinle says that although all dyes will fade over time, if Kodachrome is stored properly it can be good for up to 100 years. The film’s archival abilities, coupled with its comparative ease of use, made it the dominant film for both professionals and amateurs for most of the 20th century. Kodachrome captured a color version of the Hindenburg’s fireball explosion in 1936. It accompanied Edmund Hillary to the top of Mount Everest in 1953. Abraham Zapruder was filming with 8-mm Kodachrome in Dallas when he accidentally captured President Kennedy’s assassination. National Geographic photographer Steve McCurry used it to capture the haunting green-gray eyes of an Afghan refugee girl in 1985 in what is still the magazine’s most enduring cover image.

For 20 years, anyone wishing to develop Kodachrome film had to send it to a Kodak laboratory, which controlled all processing. In 1954, the Department of Justice declared Kodachrome-processing a monopoly, and the company agreed to allow other finishing plants to develop the film; the price of a roll of film — which previously had the processing cost added into it — fell roughly 43%.

Kodachrome’s popularity peaked in the 1960s and ’70s, when Americans’ urge to catalog every single holiday, family vacation and birthday celebration hit its stride. Kodachrome II, a faster, more versatile version of the film, came out in 1961, making it even more appealing to the point-and-shoot generation. Super 8, a low-speed fine-grain Kodachrome movie film, was released in 1965 — and was used to film seemingly every wedding, beach holiday and backyard barbecue for the next decade. (Aficionados can check out the opening credits of the ’80s coming-of-age drama The Wonder Years for a quick hit of nostalgia.) When Paul Simon sang, “Mama, don’t take my Kodachrome away” in 1973, Kodak was still expanding its Kodachrome line, and it was hard to believe that it would ever disappear. But by the mid-1980s, video camcorders and more easily processed color film from companies like Fuji and Polaroid encroached on Kodachrome’s market share, and the film fell into disfavor. Compared to the newer technology, Kodachrome was a pain to develop. It required a large processing machine and several different chemicals and over a dozen processing steps. The film would never, ever be able to make the “one-hour photo” deadline that customers increasingly came to expect. Finally in the early 2000s came the digital-photography revolution; digital sales today account for more than 70% of Kodak’s revenue.

Kodak quit the film-processing business in 1988 and slowly began to disengage from film-manufacturing. Super 8 went by the wayside in 2007. By 2008 Kodak was producing only one Kodachrome film run — a mile-long sheet cut into 20,000 rolls — a year, and the number of centers able to process it had declined precipitously. Today, Steinle’s Kansas store processes all of Kodak’s Kodachrome film — if you drop a roll off at your local Wal-Mart, it will be developed at Dwayne’s Photo — and though it is the only center left in the world, the company processes only a few hundred rolls a day.

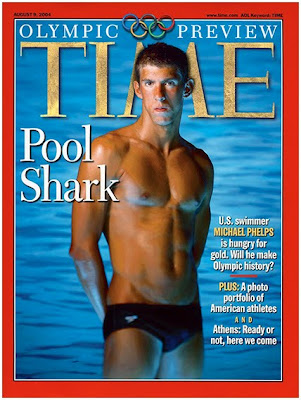

Kodachrome 64 slide film, discontinued on June 22, was the last type of true Kodachrome available — although the company expects existing stocks to last well into the fall. Kodak plans to donate the last remaining rolls of Kodachrome film to the George Eastman House’s photography museum. One of them will be symbolically shot by McCurry — although the famed photographer gave up the format long ago. In fact, McCurry’s photographic career perfectly traces the rise and fall of Kodak film. He shot his iconic Afghan-girl portrait on Kodachrome and returned 17 years later to photograph the same woman with Kodak’s easier-to-develop Ektachrome. Now, he relies on digital.

Read more: http://www.time.com/time/arts/article/0,8599,1906503,00.html#ixzz2IRUPYIvR

Photo copyright: DJ Florek

http://dave-florek.artistwebsites.com/index.html

/Marc%20McAndrews%20brothels/038_MMA_BR193Cindy_flat.jpg.CROP.thumbnail-small.jpg)

/Michael%20Jang%20weather%20people/sw71.jpg.CROP.thumbnail-small.jpg)

/Brian%20Finke%20bodybuilders/BrianFinke_Bodybuilding14_09.jpg.CROP.thumbnail-small.jpg)

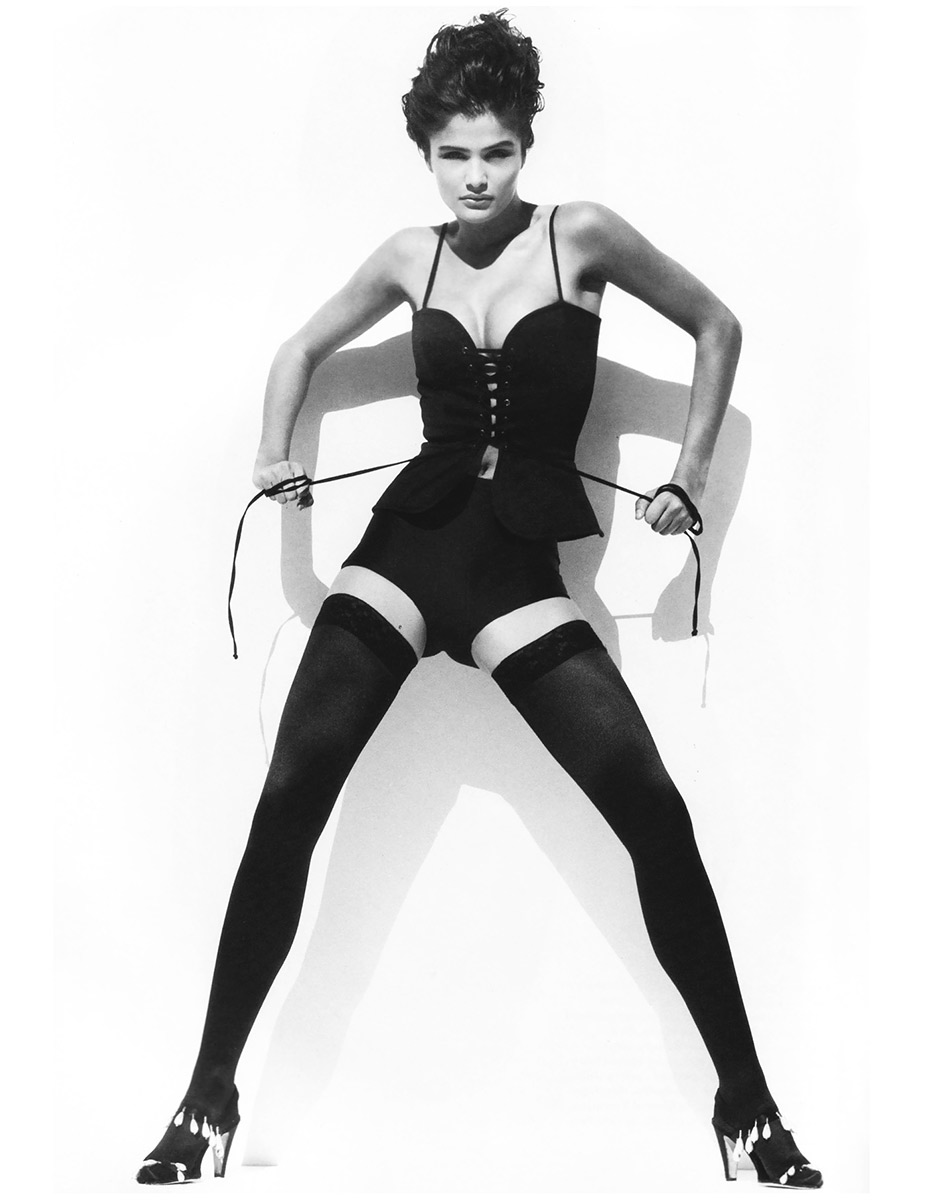

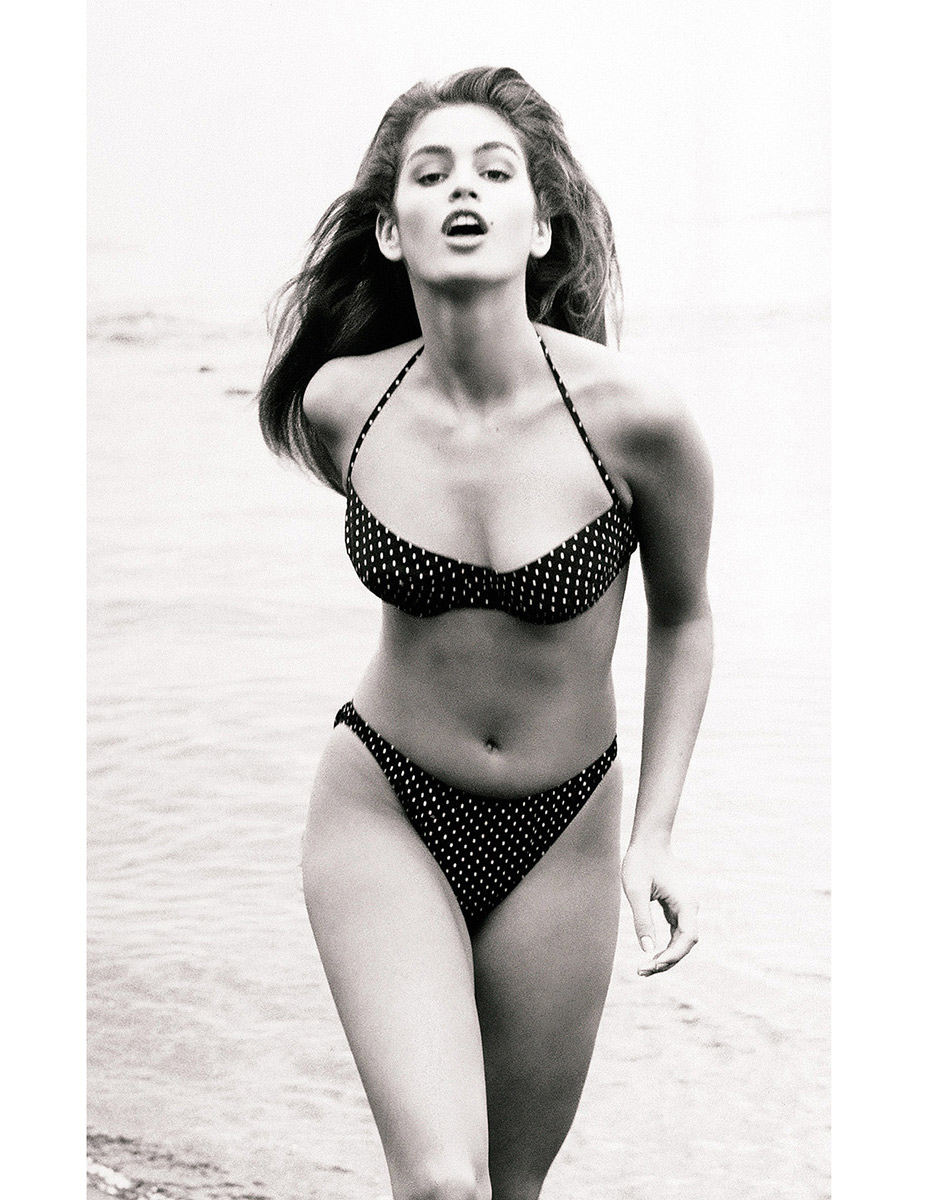

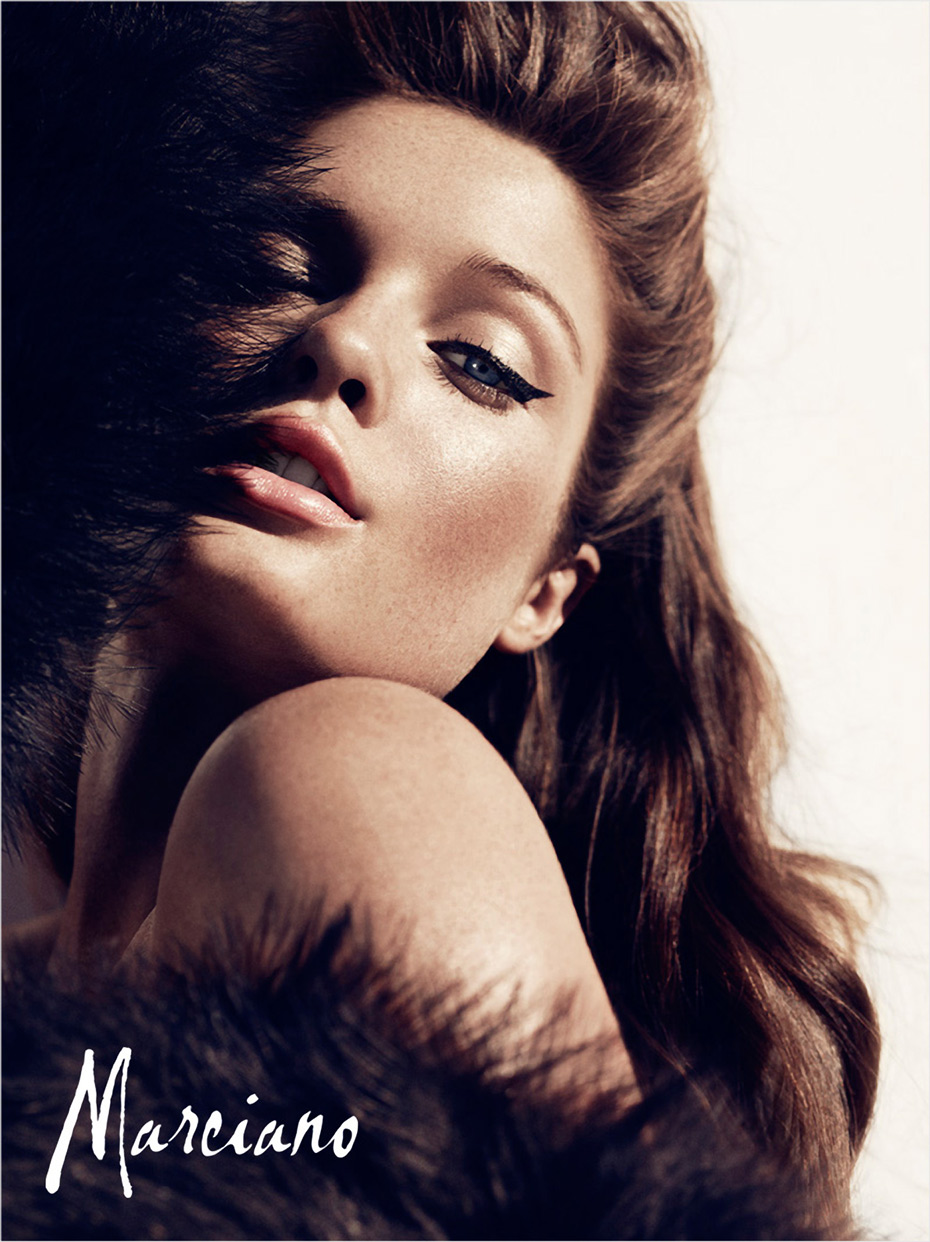

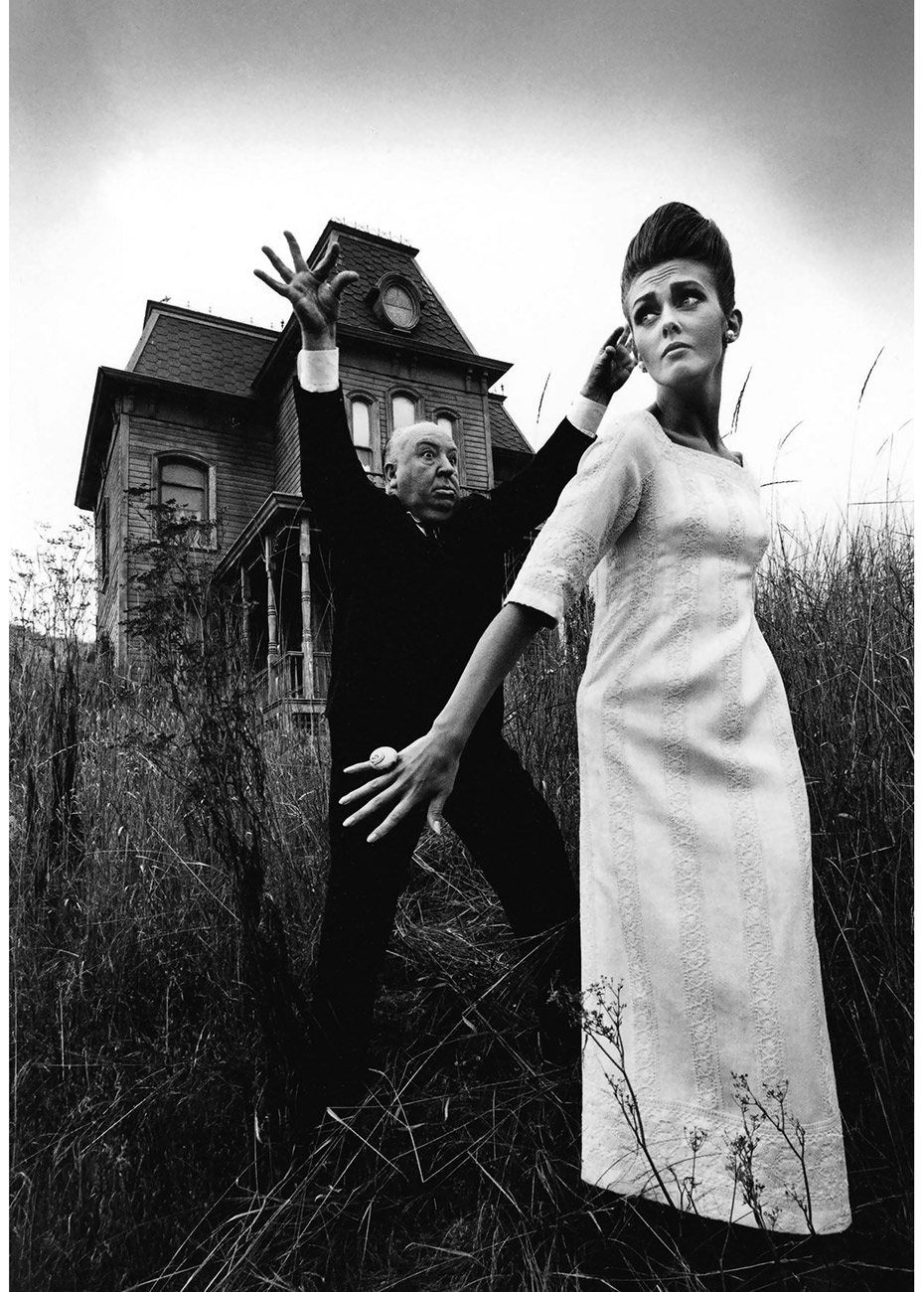

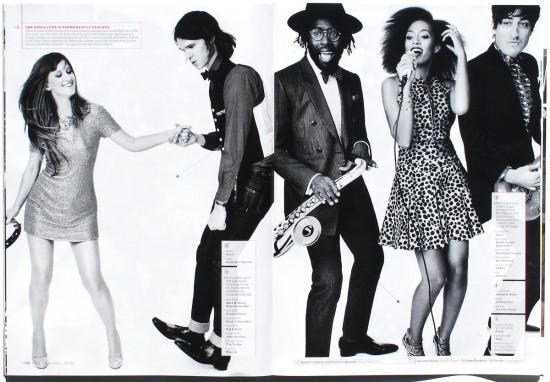

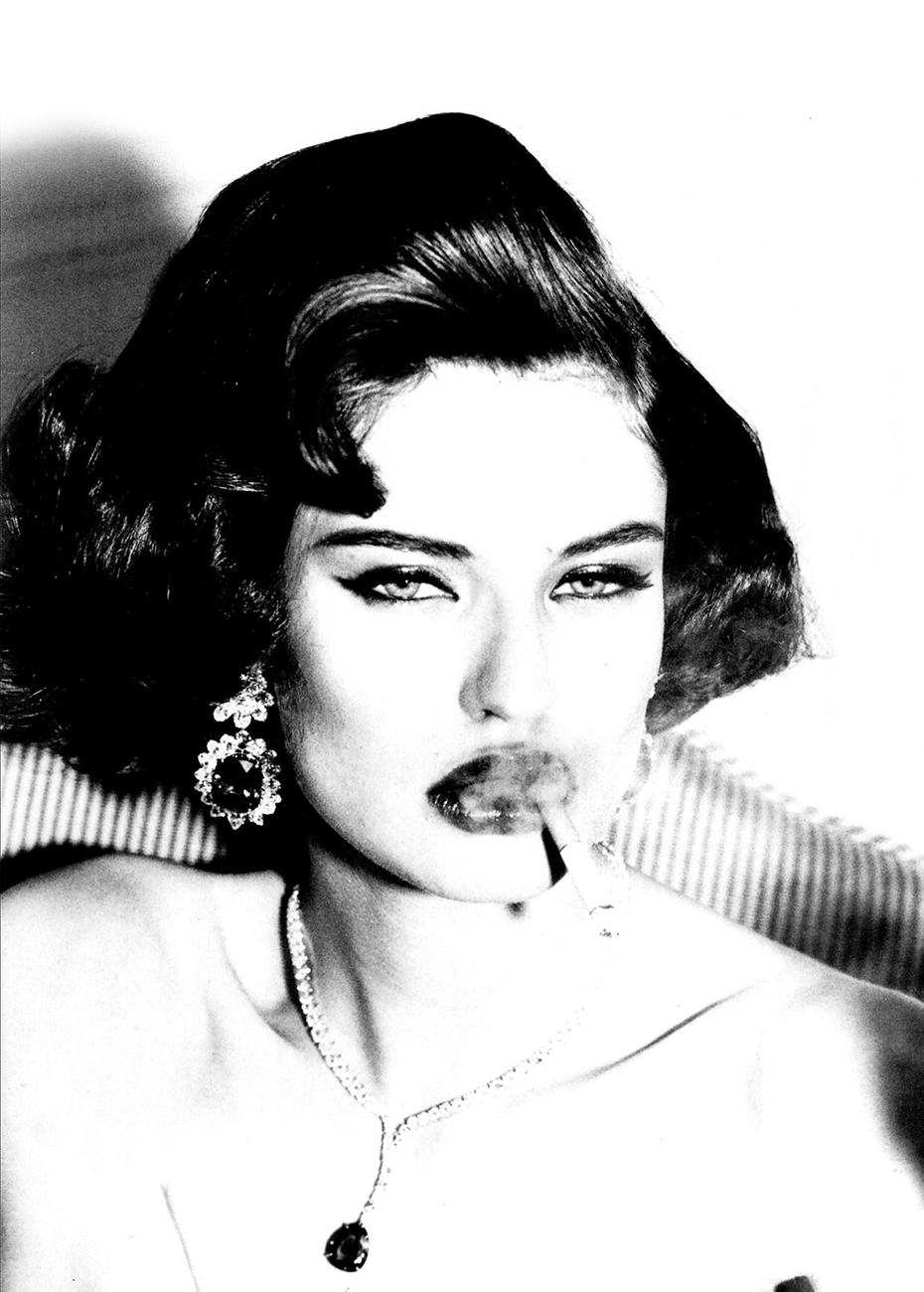

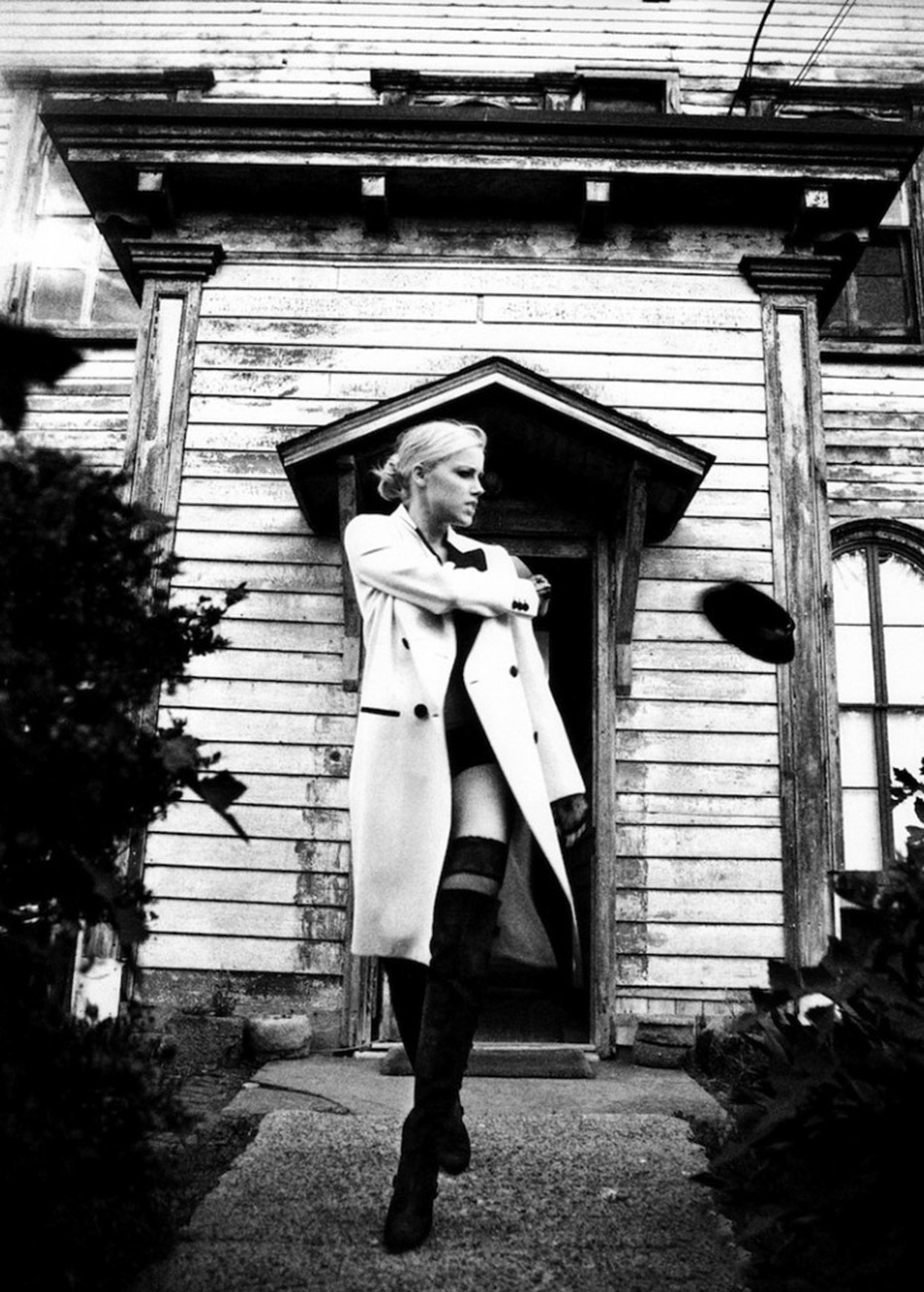

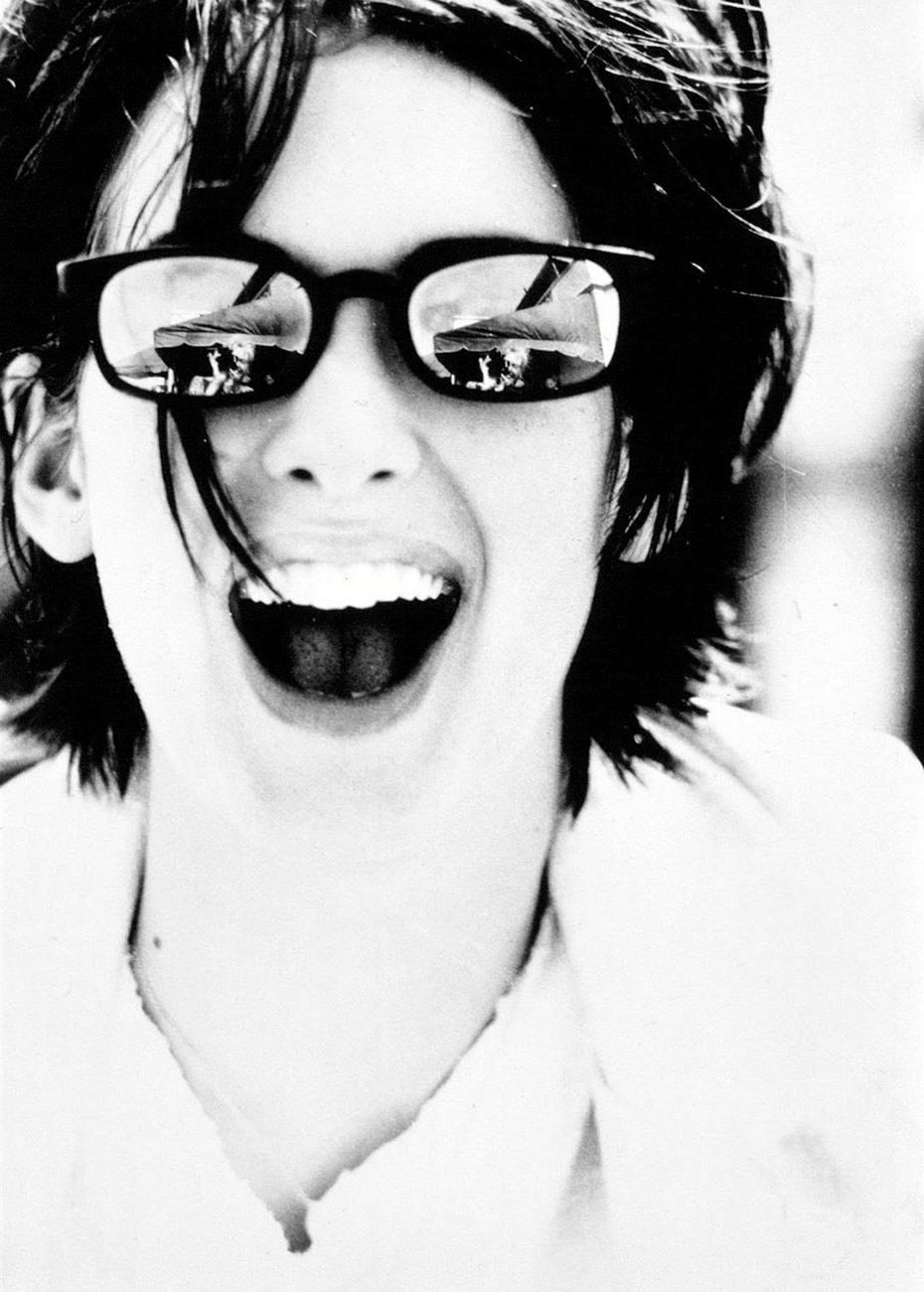

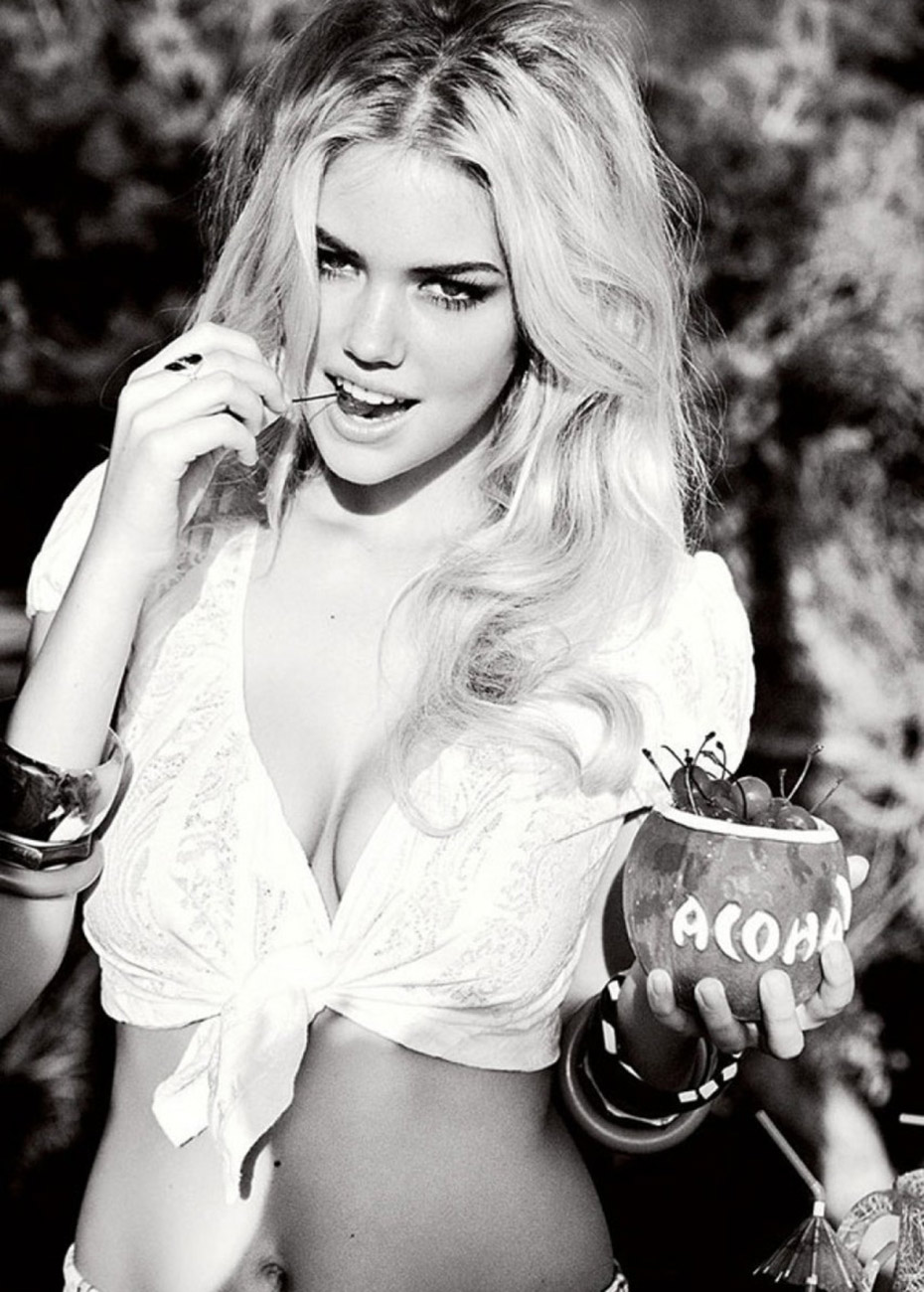

In his life and work, Herb Ritts was drawn to clean lines and strong forms. This graphic simplicity allowed his images to be read and felt instantaneously. They often challenged conventional notions of gender or race. Social history and fantasy were both captured and created by his memorable photographs of noted individuals in film, fashion, music, politics and society.

In his life and work, Herb Ritts was drawn to clean lines and strong forms. This graphic simplicity allowed his images to be read and felt instantaneously. They often challenged conventional notions of gender or race. Social history and fantasy were both captured and created by his memorable photographs of noted individuals in film, fashion, music, politics and society.