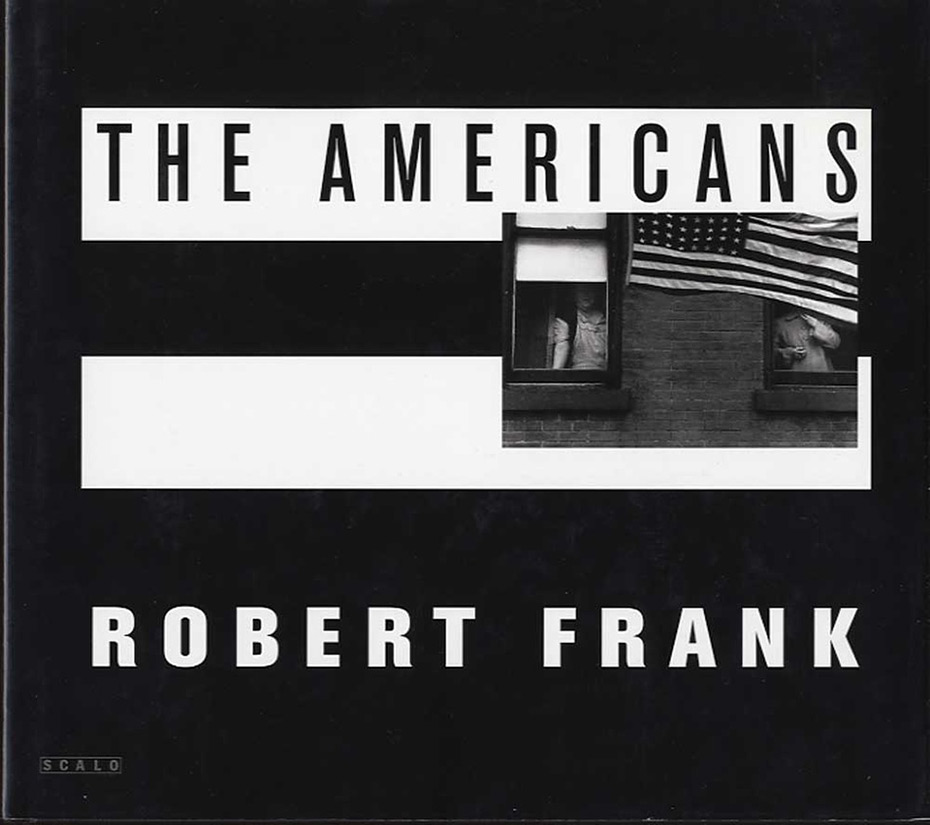

Robert Frank (born November 9, 1924), born in Zürich, Switzerland, is an important figure in American photography and film. His most notable work, the 1958 photobook titled The Americans, was influential, and earned Frank comparisons to a modern-day de Tocqueville for his fresh and skeptical outsider’s view of American society. Frank later expanded into film and video and experimented with compositing and manipulating photographs.

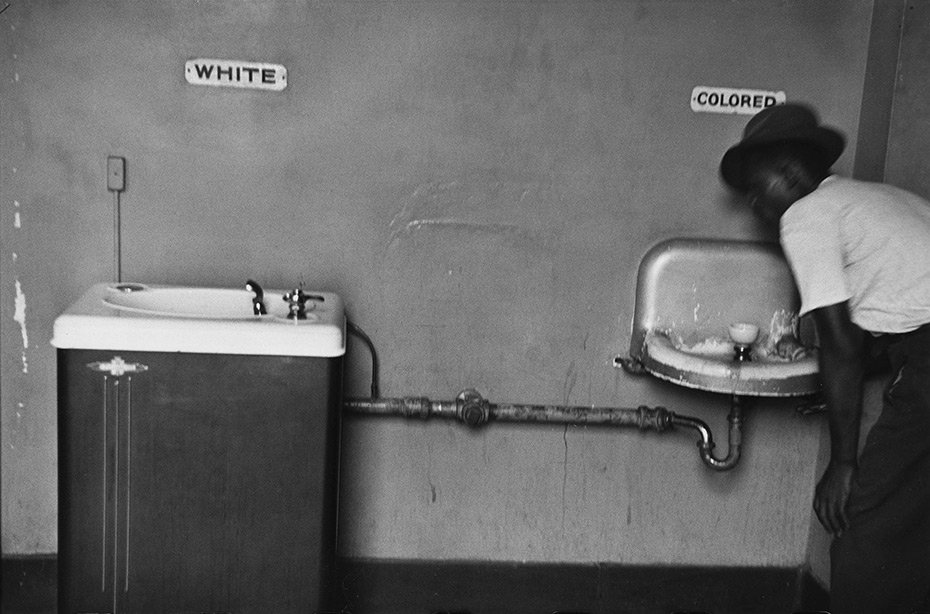

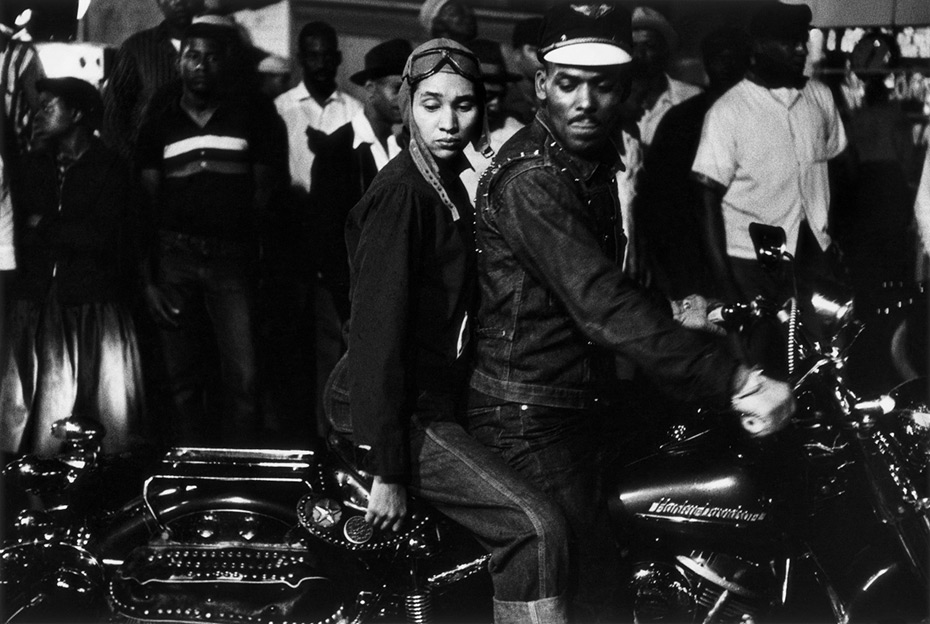

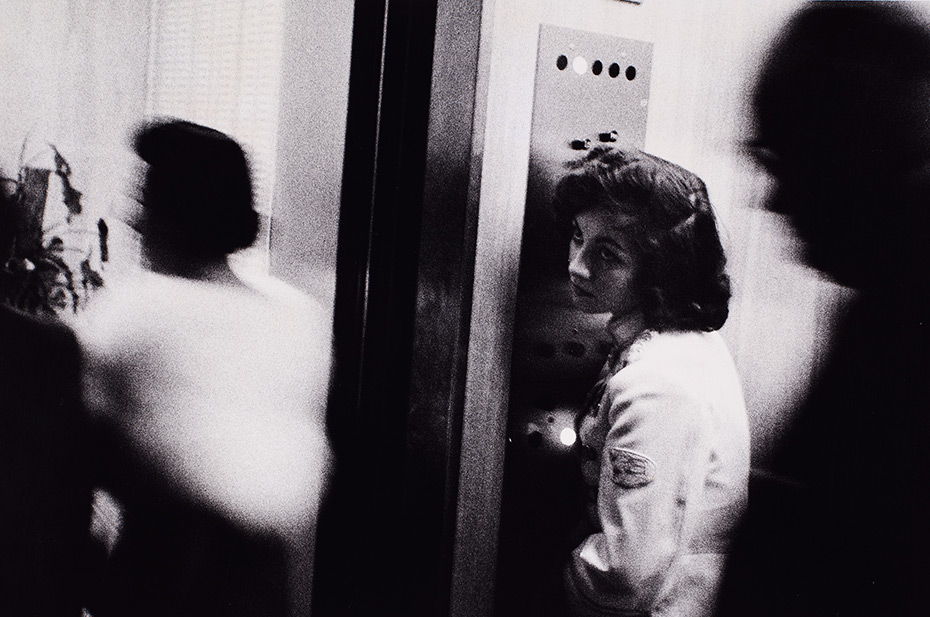

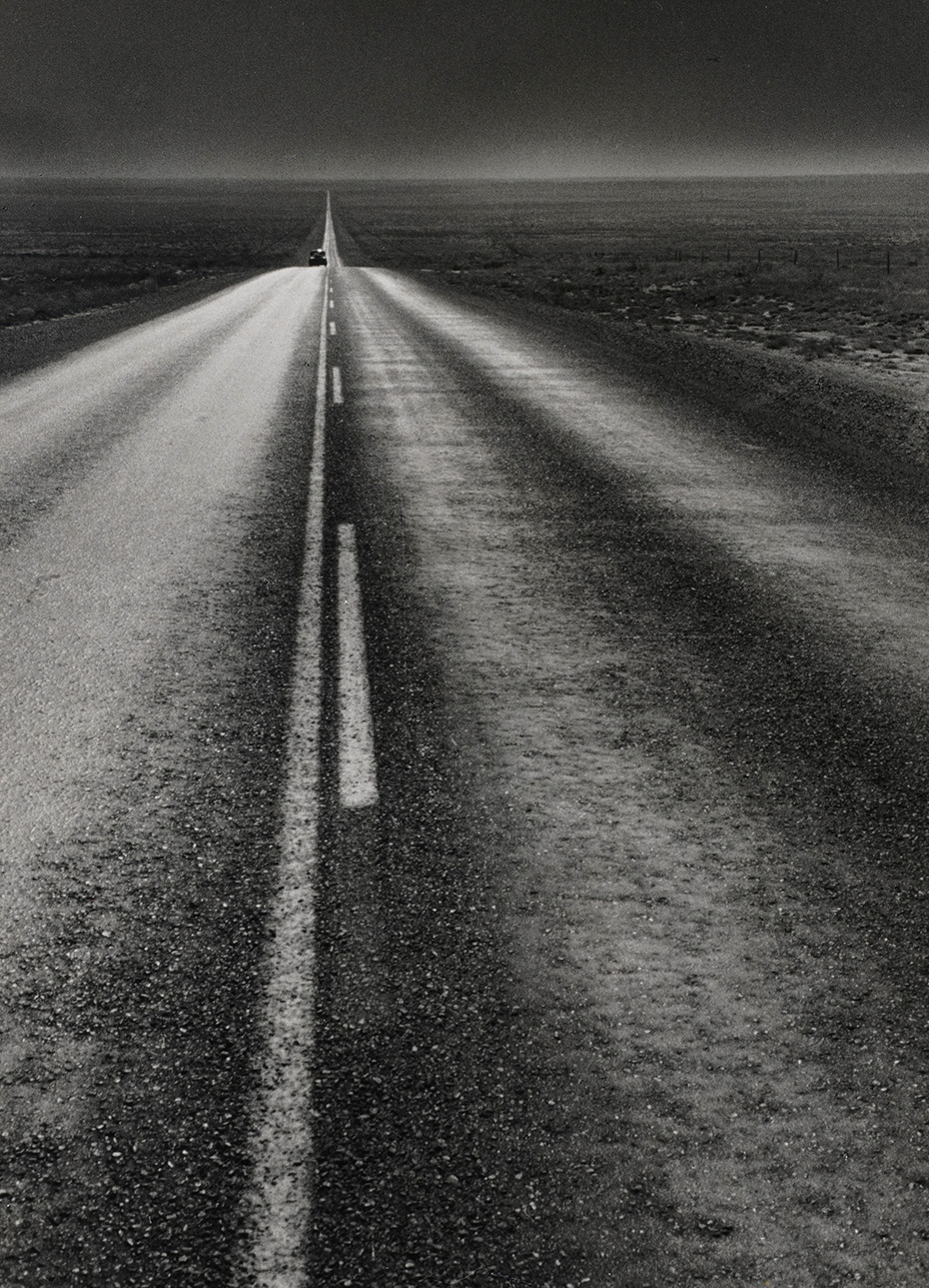

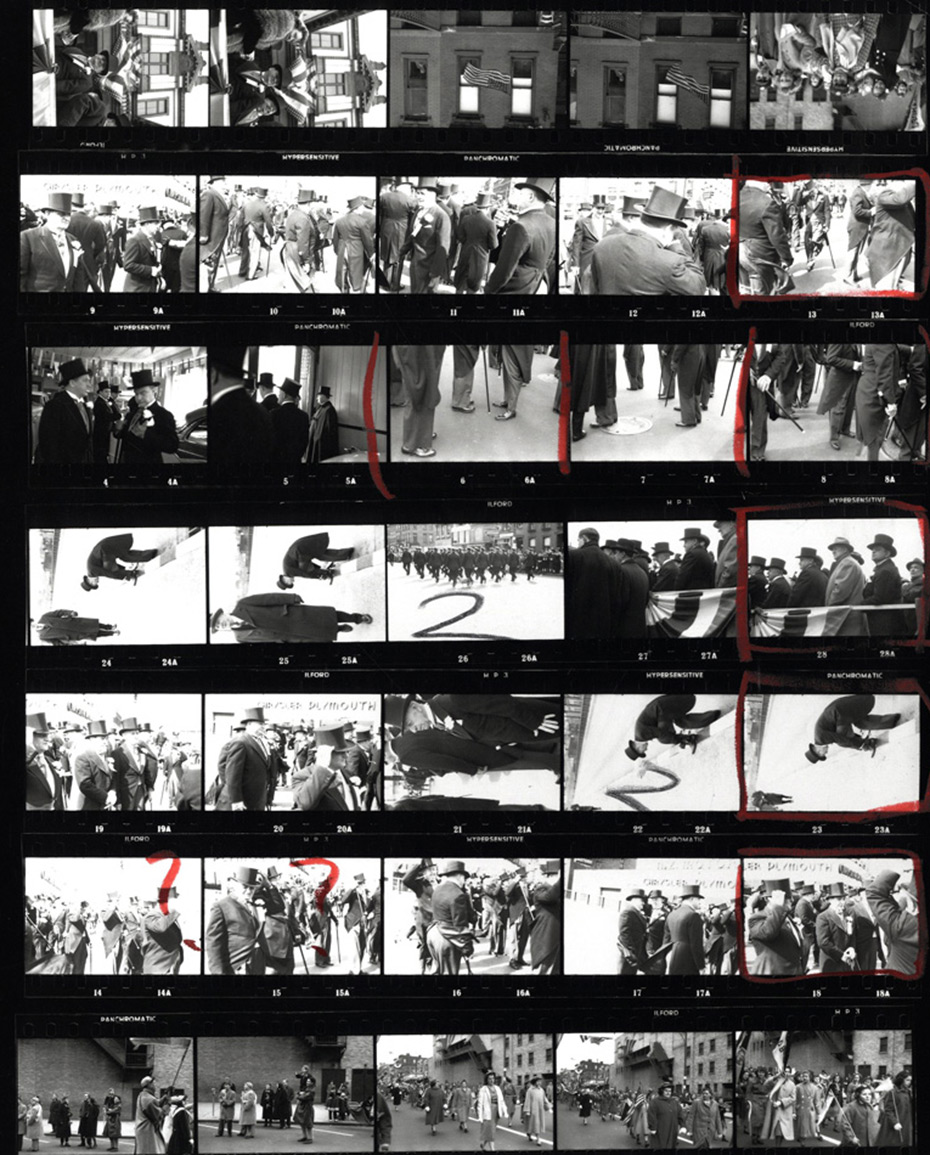

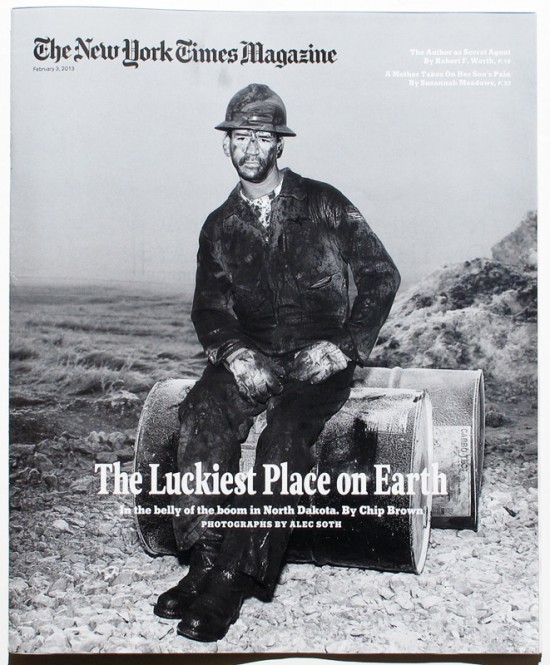

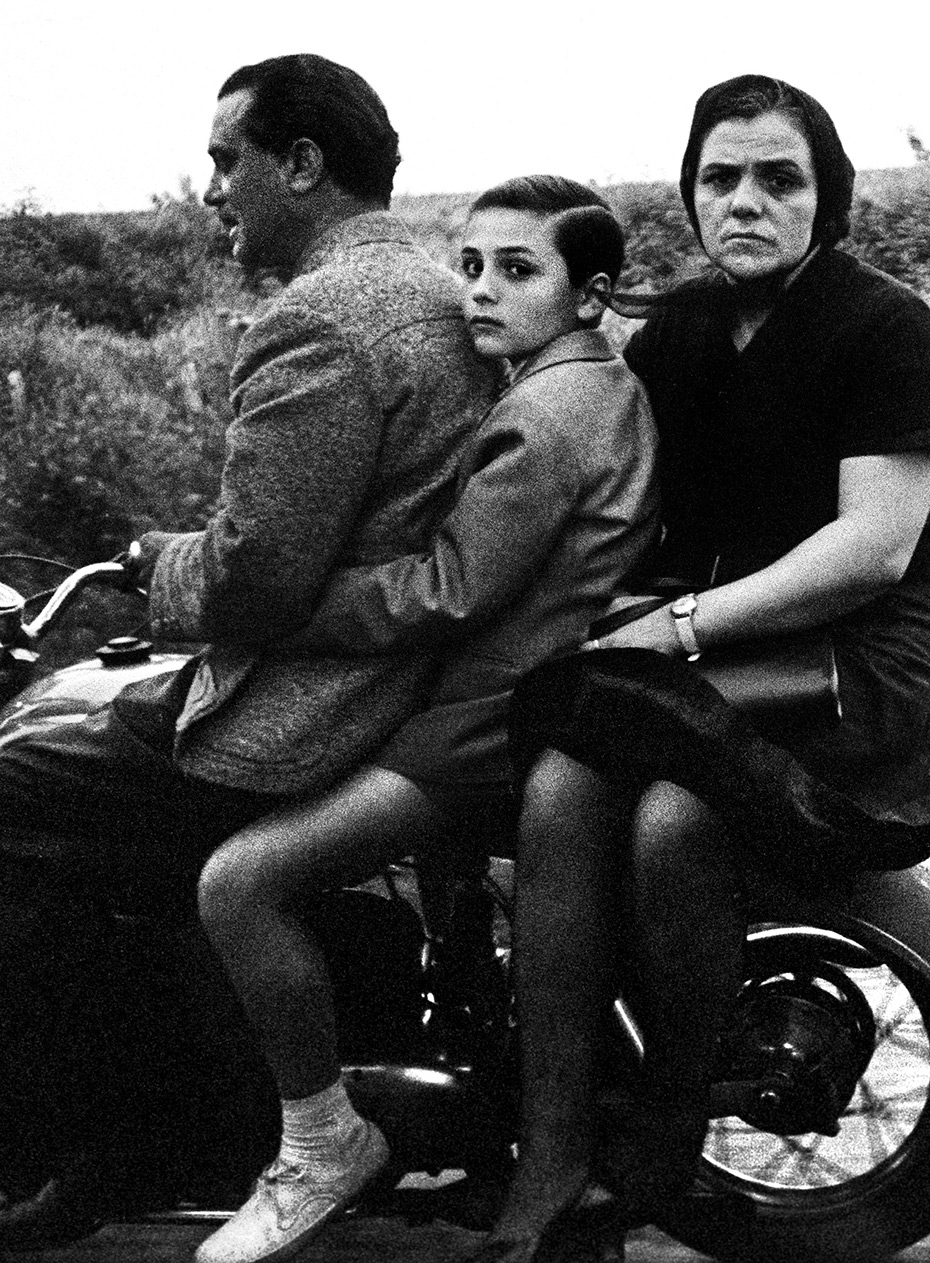

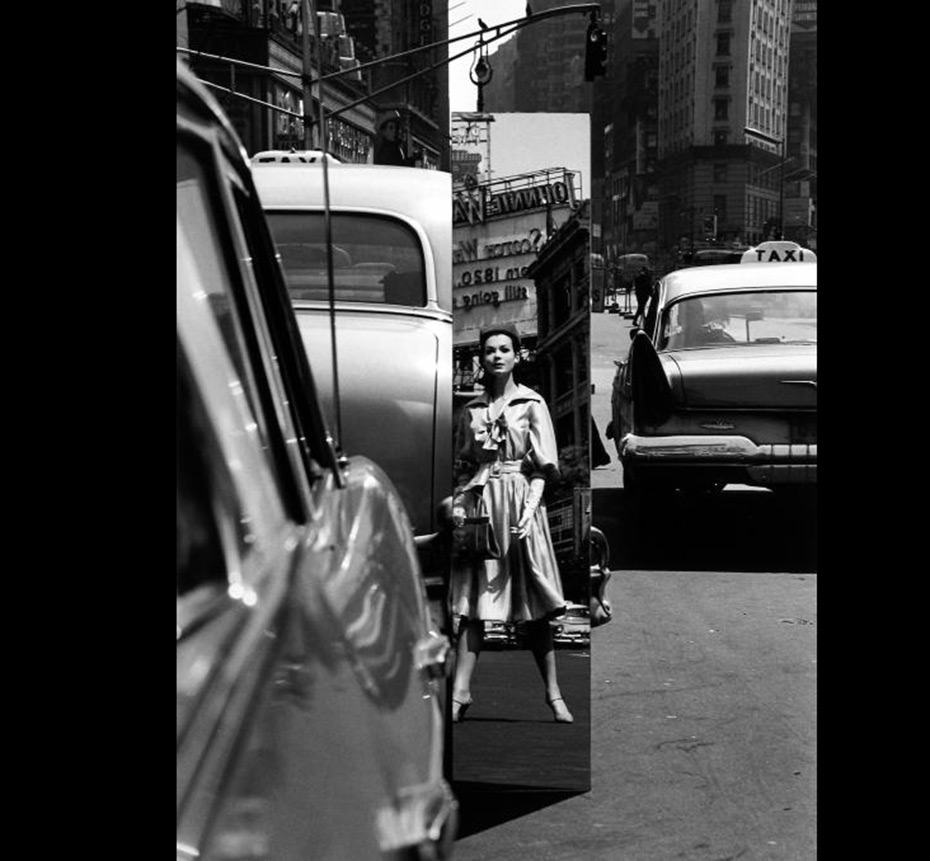

“The Americans” was published in Paris. Robert Frank’s book of 83 black-and-white images, extracted from more than 28,000 individual shots taken on road trips between 1955 and 1957, did not reflect the apple-pie vistas of Eisenhower suburbia. The Swiss photographer took a novel, jaundiced view of the country, catching lonely, vagabond faces with unusual angles, jukeboxes alight in half-empty bars, lost highways, and short-order melancholy.

After the underground success of “The Americans” in the late ’50s, Mr. Frank began to concentrate on art films and videos, such as 1959’s beatnik reverie “Pull My Daisy.” He captured a society in flux, one making a jarring transition from contentment to discontentment, and he did so from uncommon perspectives. One oft-cited review deemed his work a “meaningless blur.” But as Jack Kerouac (who served as narrator on “Pull My Daisy”) wrote in his introduction to the Grove Press edition of “The Americans,” published in 1959, “Robert Frank. Swiss, unobtrusive, nice, with that little camera that he raises and snaps with one hand he sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film, taking rank among the great tragic poets of the world.”

What is most compelling about “The Americans” today is how what was once disturbing and revelatory gradually became iconic and even romantic: Looking back from the 21st century, these scenes are what come to mind when we think about what “America” is. This is not so much in a contemporary sense, as a lot of what fills Mr. Frank’s lens — the jukeboxes, the black-and-white televisions, the convertibles with their tail fins — looks like relics of an imaginary age. But maybe because of that, and because of so much chest-thumping campaign rhetoric about one candidate’s patriotism or another’s beer-and-a-shot authenticity, it’s an extremely useful book to look at right now. These photographs have never stopped resonating.

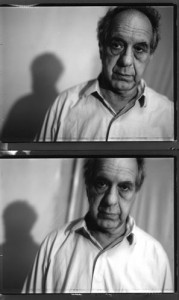

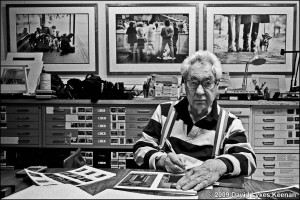

The double photo of Robert Frank at the beginning of this post was taken by Barry Kornbluh (barrykornbluh.nl)

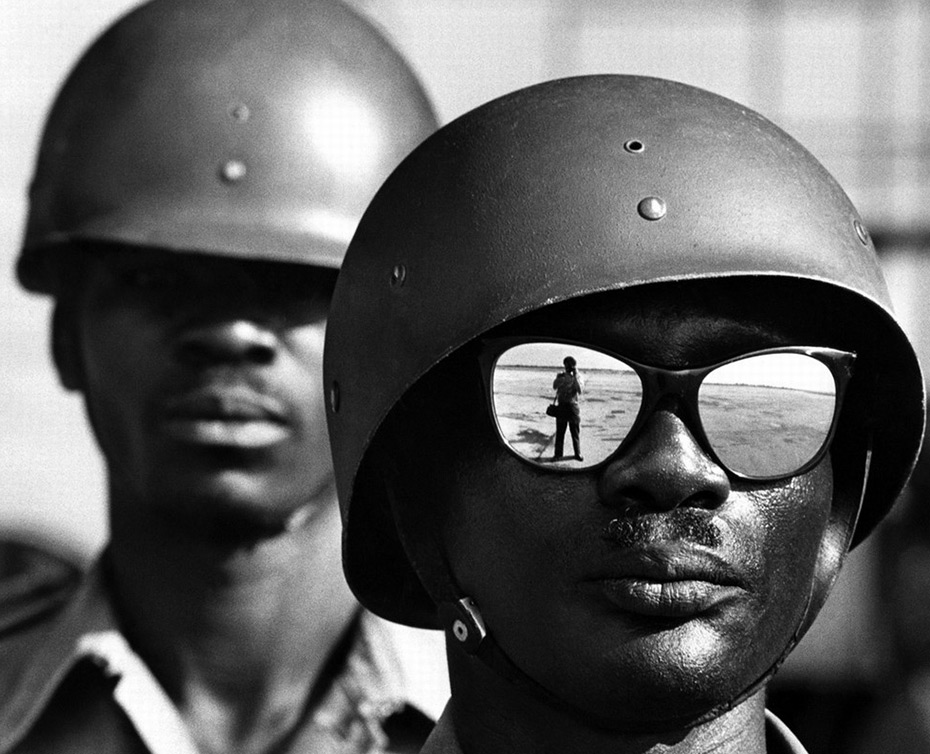

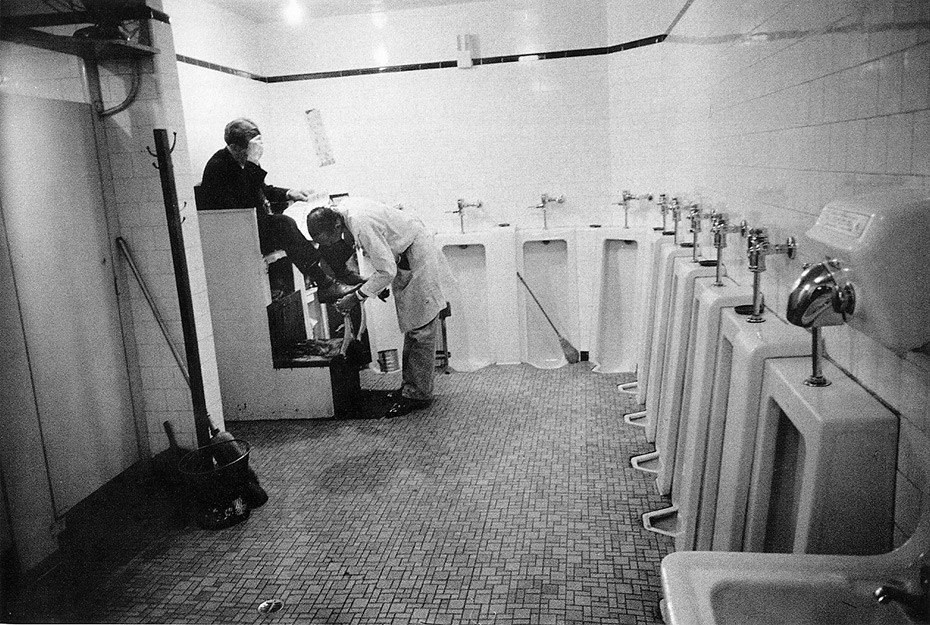

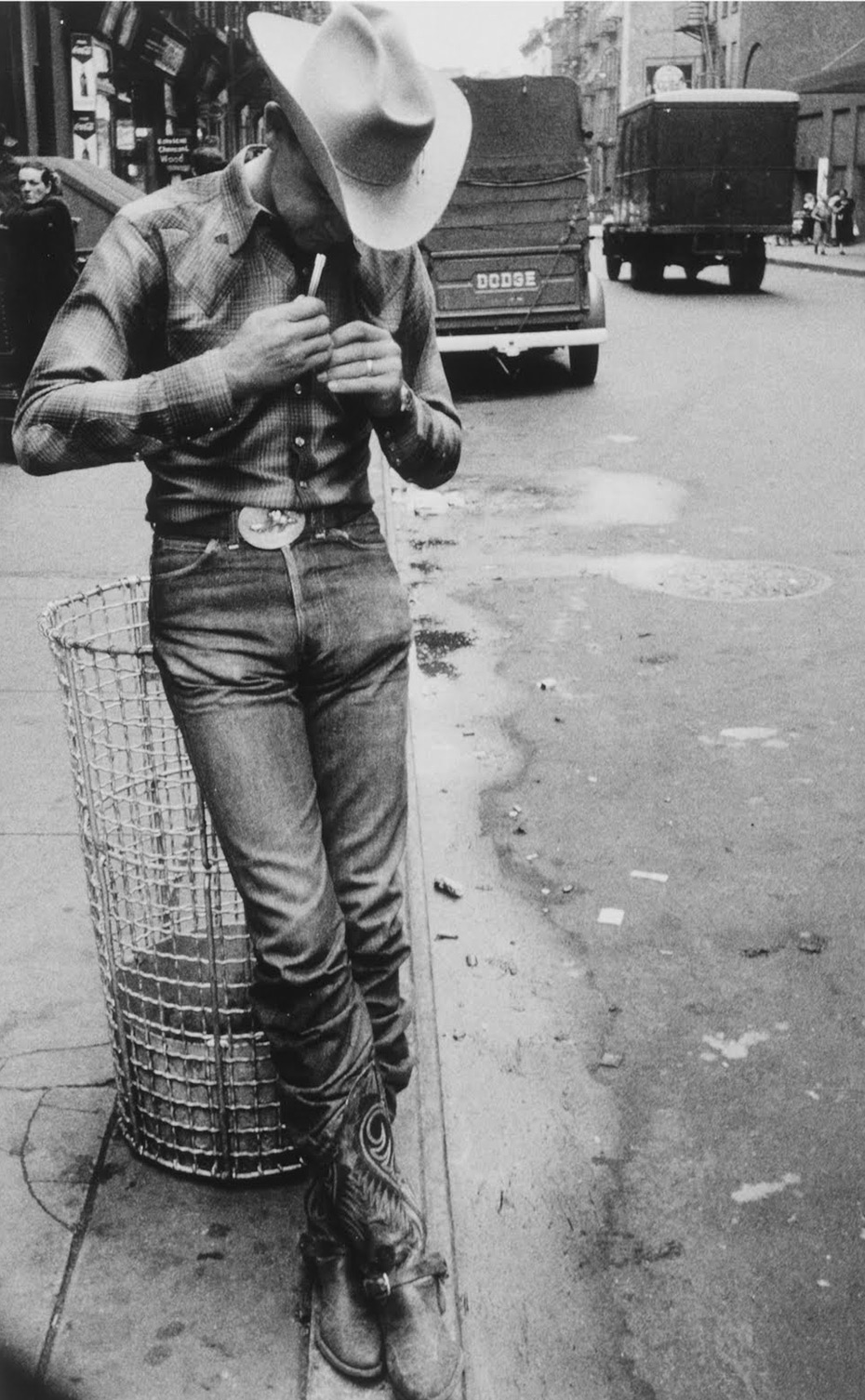

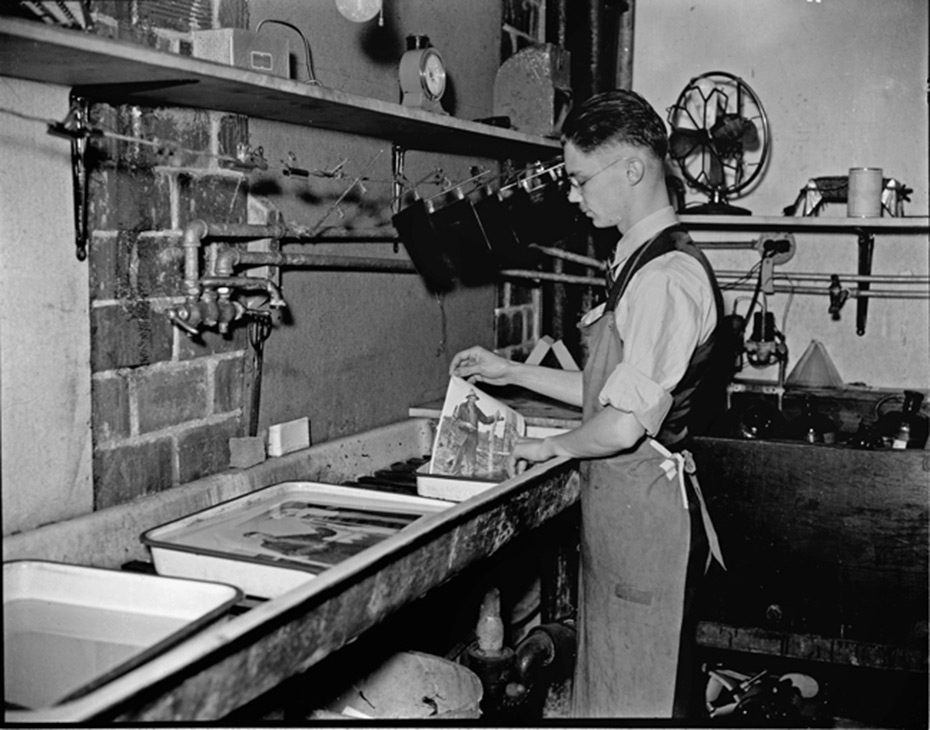

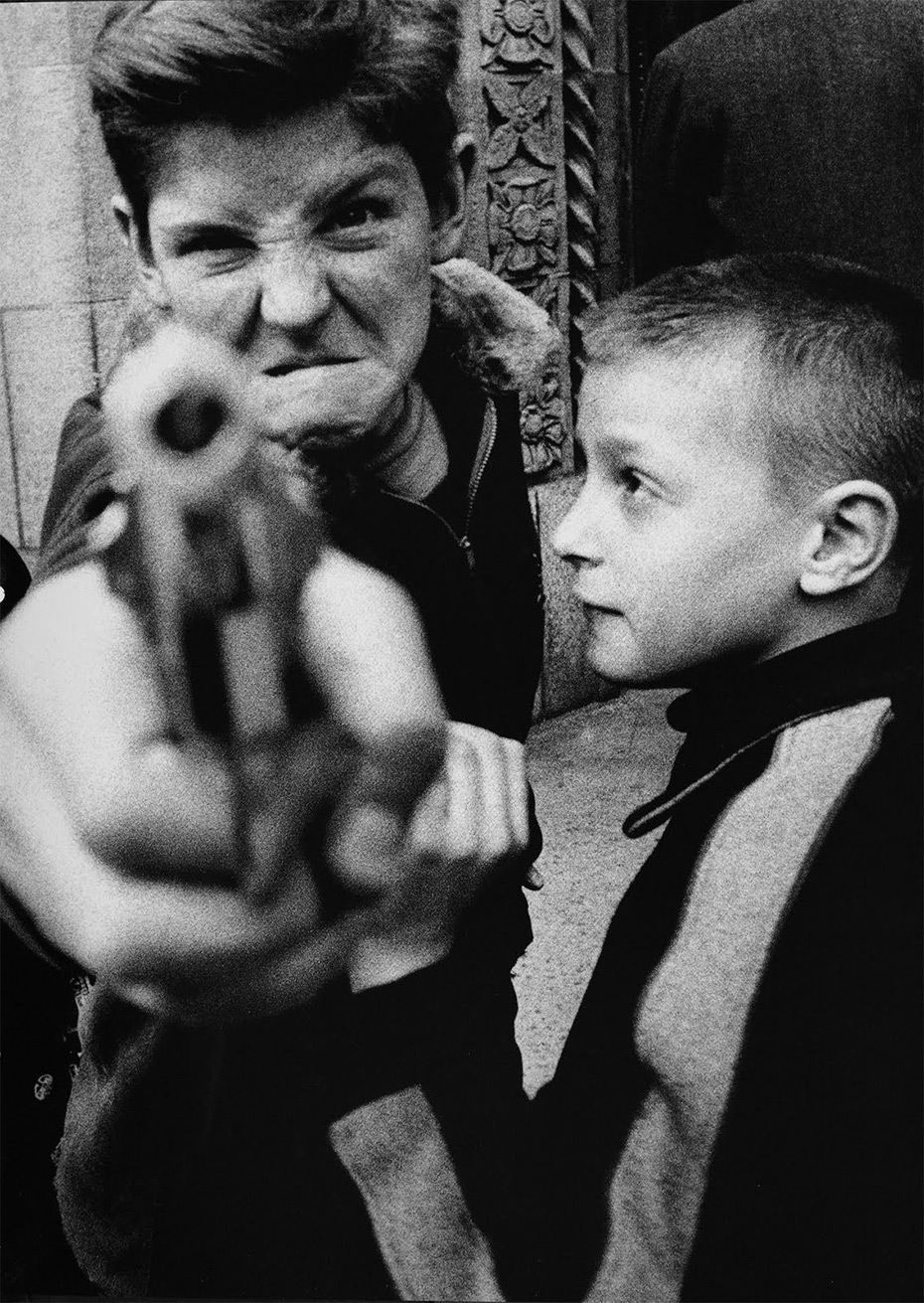

This photo (below) I originally made a mistake on posting as Robert Frank’s. I love this image and the photographer that took it is a fellow Canadian: Rob Atkins. Thanks Rob for the kind note and wicked photo!

/Anne%20Hardy/MP-HARDA-00158-A-920px.jpg.CROP.thumbnail-small.jpg)

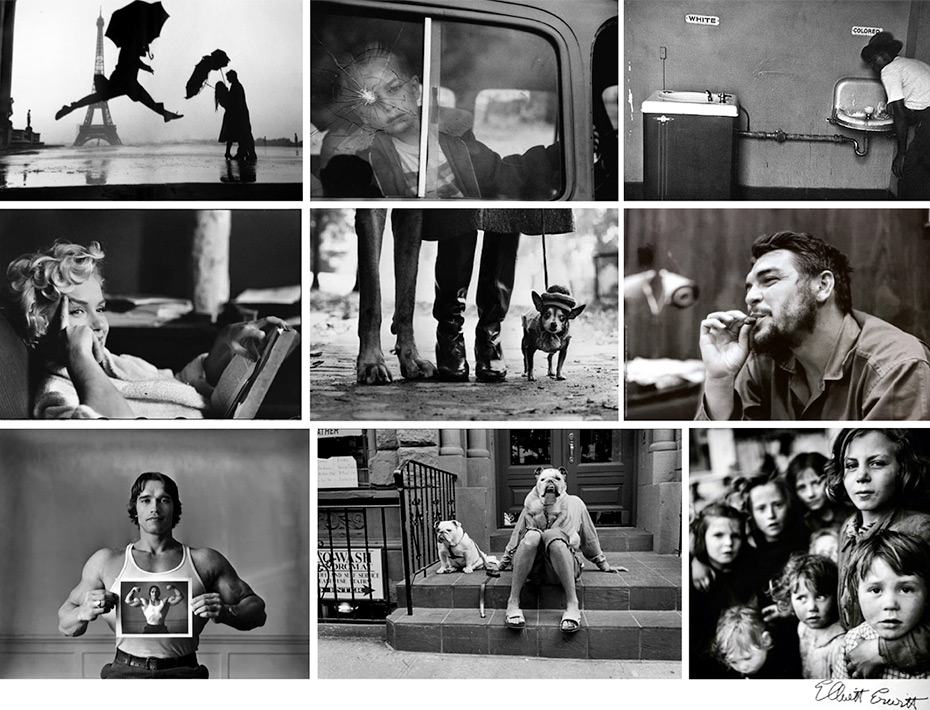

While in New York, Erwitt met Edward Steichen, Robert Capa and Roy Stryker, the former head of the Farm Security Administration. Stryker initially hired Erwitt to work for the Standard Oil Company, where he was building up a photographic library for the company, and subsequently commissioned him to undertake a project documenting the city of Pittsburgh.

While in New York, Erwitt met Edward Steichen, Robert Capa and Roy Stryker, the former head of the Farm Security Administration. Stryker initially hired Erwitt to work for the Standard Oil Company, where he was building up a photographic library for the company, and subsequently commissioned him to undertake a project documenting the city of Pittsburgh.