Artist Richard Nicholson has set out to capture these fast-disappearing spaces, photographing darkrooms – and the memories they hold – across London. View the video here: http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/video/2011/jan/14/photographing-death-darkroom-video

Richard Nicholson spent three years photographing commercial photographic darkrooms in London. When he began his project in 2006, there were more than 200 thriving darkrooms dotted around the city; when he completed it in 2009, there were 12.

“When I started as a young photographer about 10 years ago,” he says, “I’d go to Photofusion in Brixton or Joe’s Basement in Soho and these places would be bustling with young photographers. Often, you had to book days, sometimes weeks, in advance. Now the darkrooms that have survived are quiet and business is slow. The London labs where you could drop film off have all but disappeared – Joe’s Basement has gone and so have Primary [Colour], Metro Soho, Ceta, Sky and countless others. We are really witnessing the end of a photographic era.”

The coming of the digital camera has swept all before it, making the whole process of photography simpler, less labour-intensive, less costly and more technically creative. But as has been the case with music production, something has also been lost along the way, something intangible but powerful that the music writer Greg Milner called “presence”: the human element in the production of sound and images.

A small group exhibition, entitled Analog, opens at the Riflemaker gallery in London on 11 January. Its subtext is “presence”: the human ghost in the machine. The show includes Nicholson’s photographs of the last-surviving London darkrooms alongside an installation by Lewis Durham (of the young rockabilly group Kitty, Daisy & Lewis) in which he has recreated a reel-to-reel, multitracked tape studio, as well as works by interactive design duo Zigelbaum + Coelho and artist Clare Mitten, who has constructed laptop and mobile phone-like sculptures from packaging and stationery.

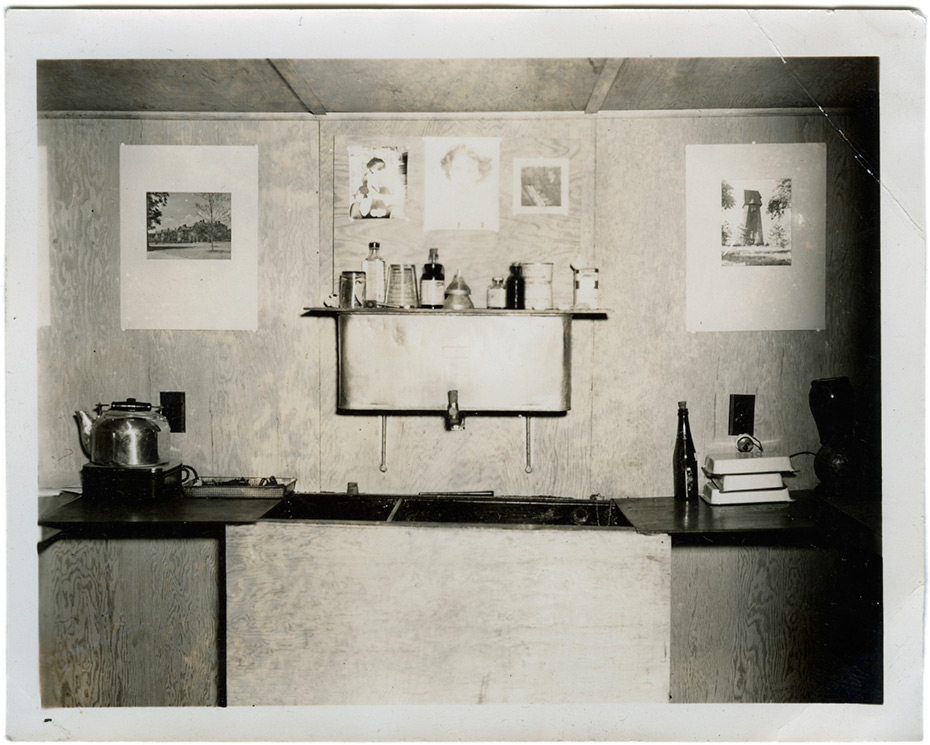

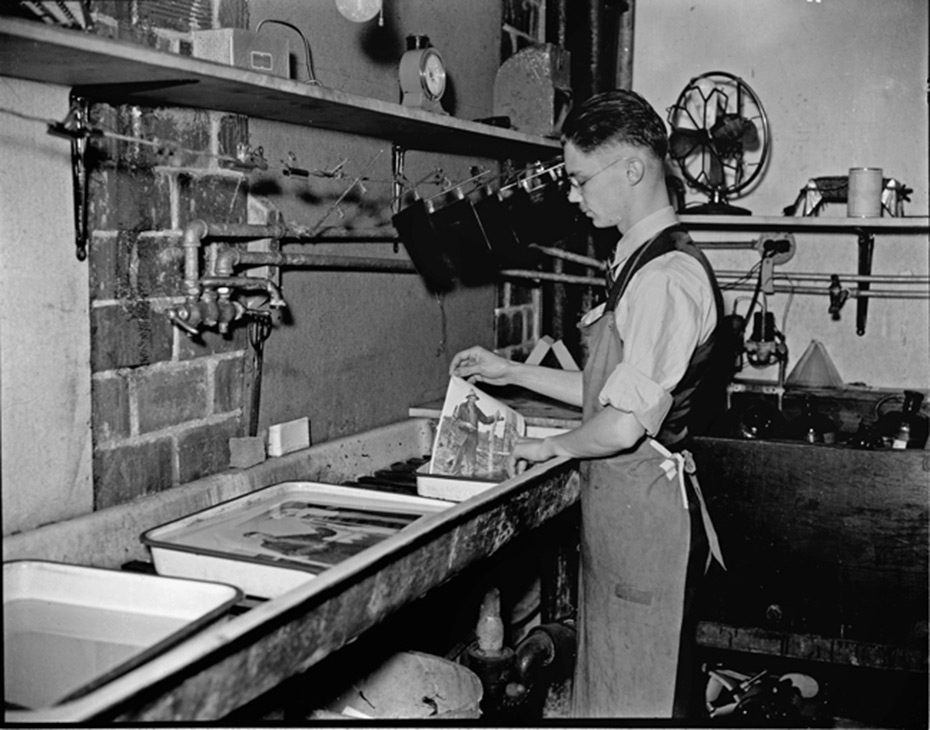

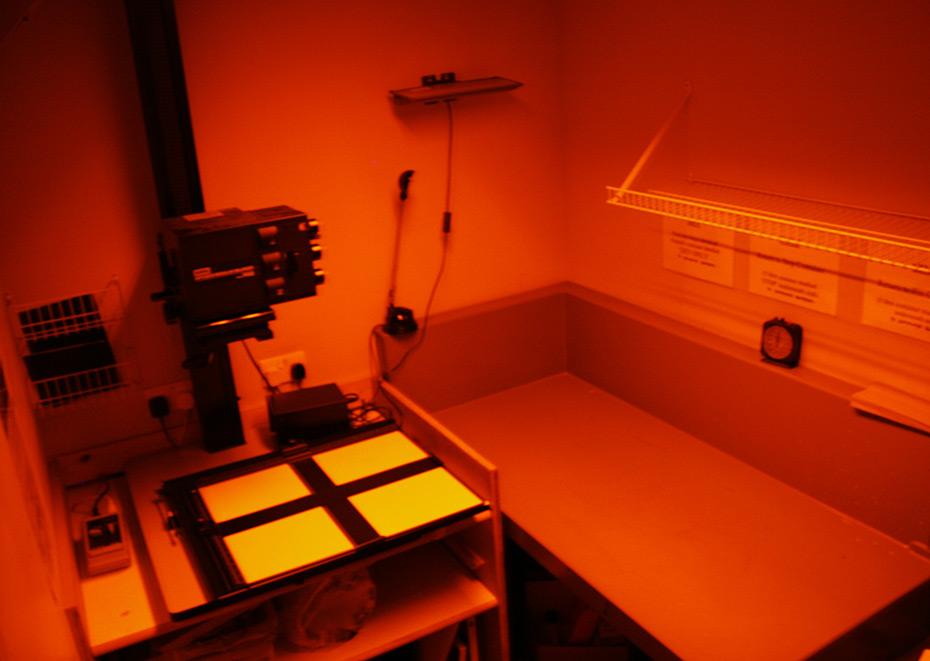

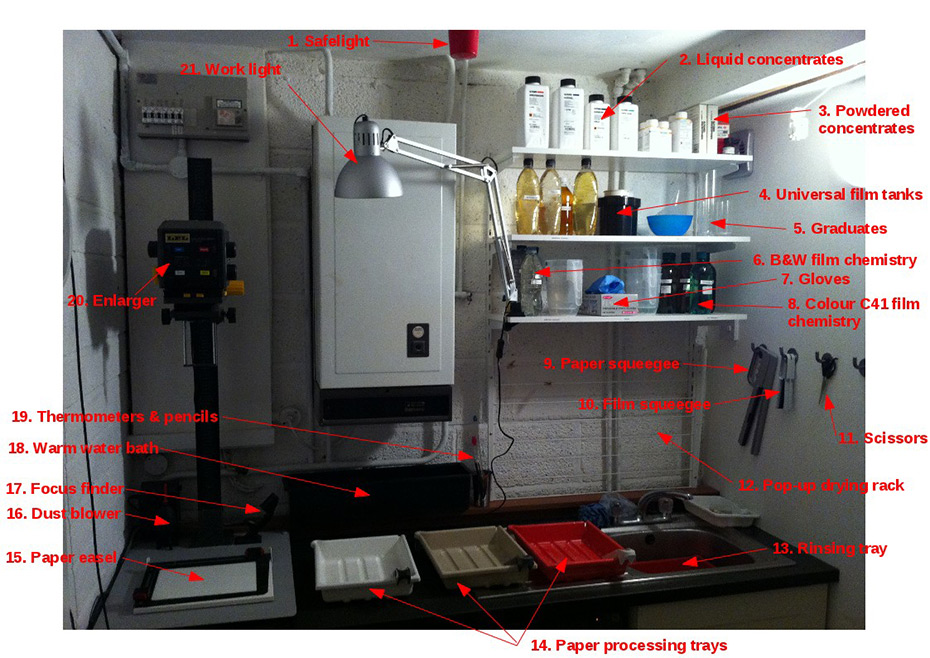

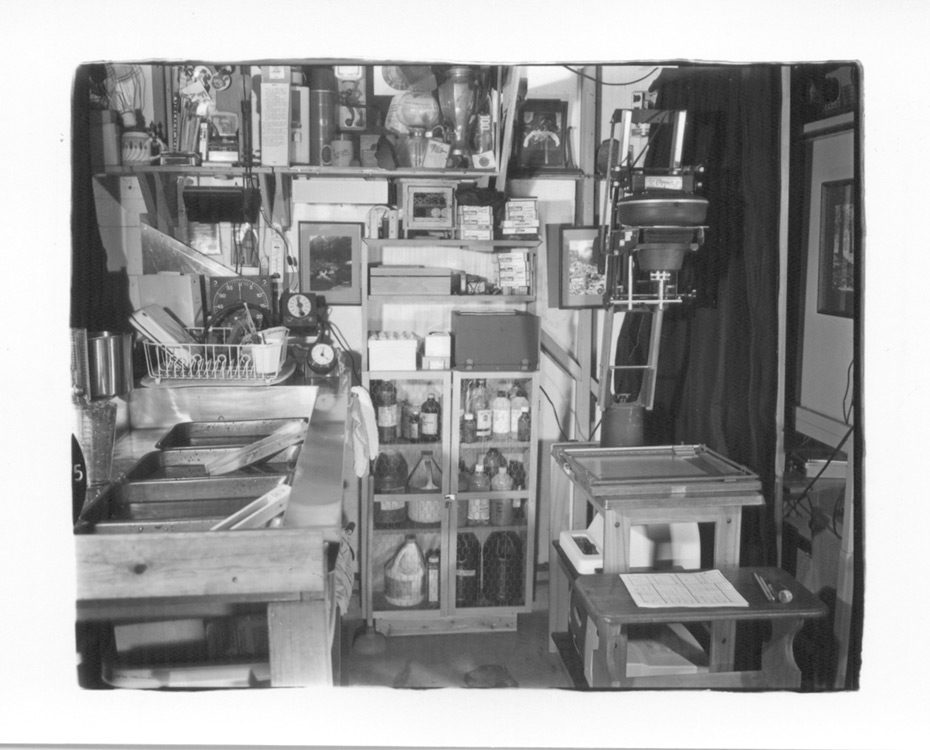

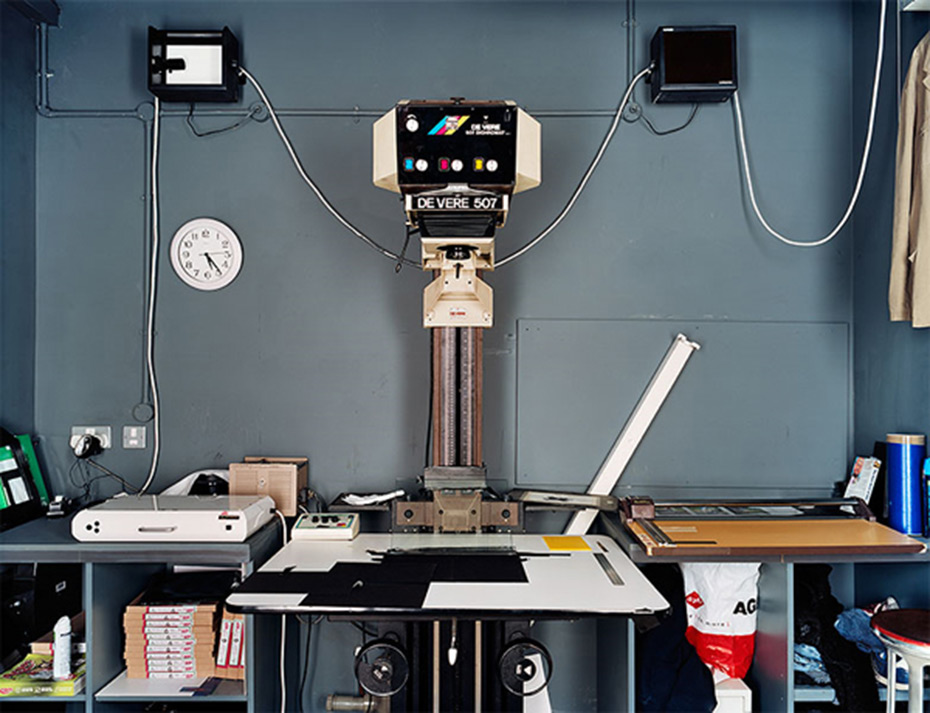

Analog is a kind of elegy for the pre-digital era of sound and photographic production and Nicholson’s prints are the most elegiac components in the mix. He has photographed each darkroom on large format film, working in total darkness with a flashgun. The result might have been what Nicholson calls “a detached typology of modernist industrial design” in which the enlarger stands at the centre, strangely human in its form. Except that these darkrooms are also human dens, full of the clutter of human endeavour – Post-it notes, piles of prints, boxes of paper, toys, rulers, marker pens and batches of photographs pinned to boards.

“I had a few epiphanies while doing this project,” says Nicholson, a soft-spoken, thin, bespectacled, ex-philosophy graduate, “and one was the realisation that the world of work, particularly a craft like darkroom printing, has becoming utterly homogenised in the digital era. Even just a few years ago, every profession had its own machinery, its tools, its language; now all we have are computers.”

Read more: http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2010/dec/26/analog-photography-gunmakers-review?intcmp=239

Below is a gallery of darkroom that bring back some great memories. (Not all of these are photographs are Richard’s)

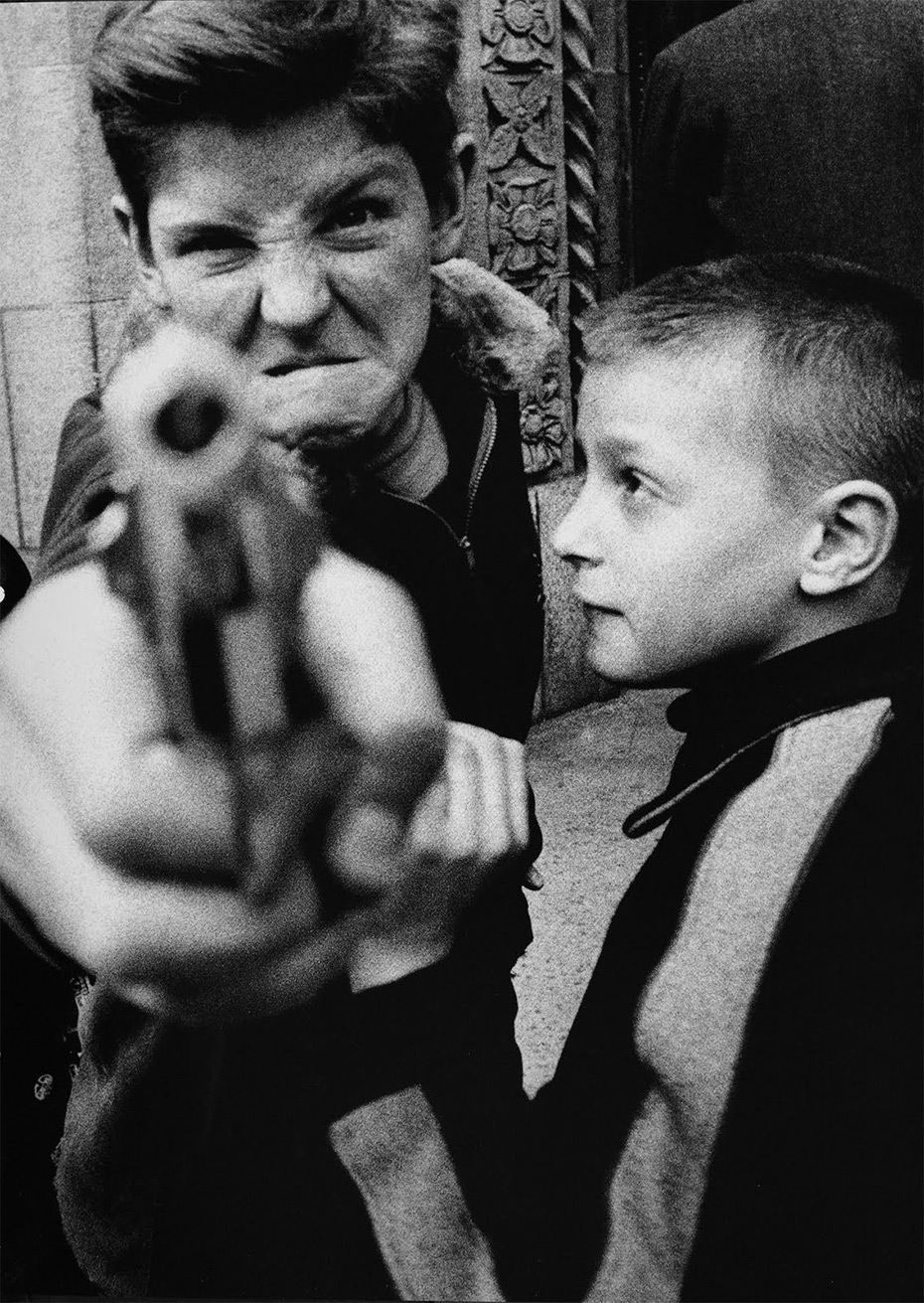

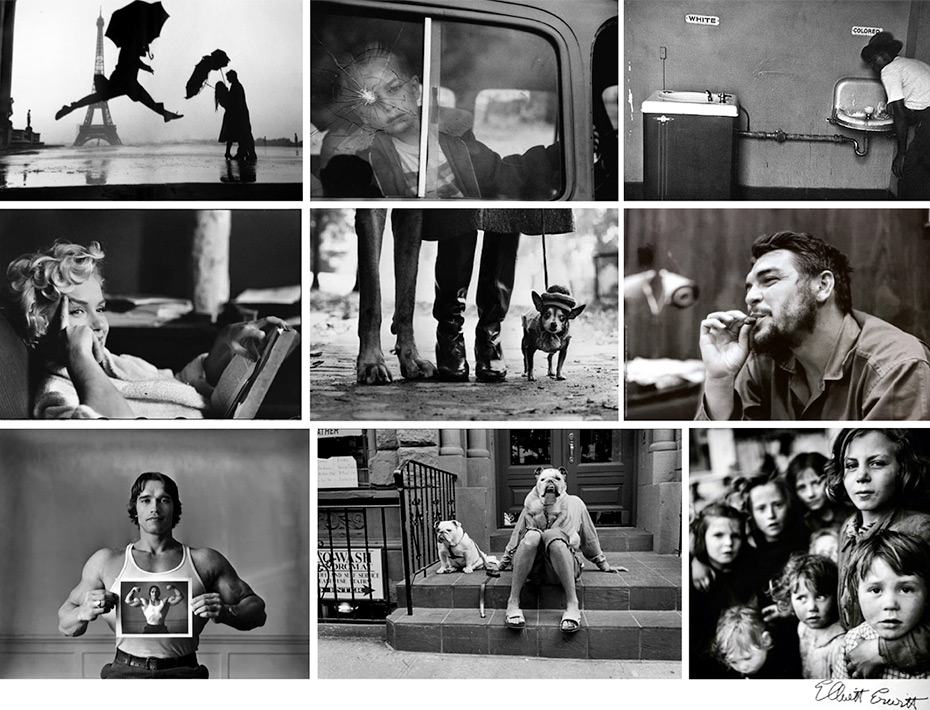

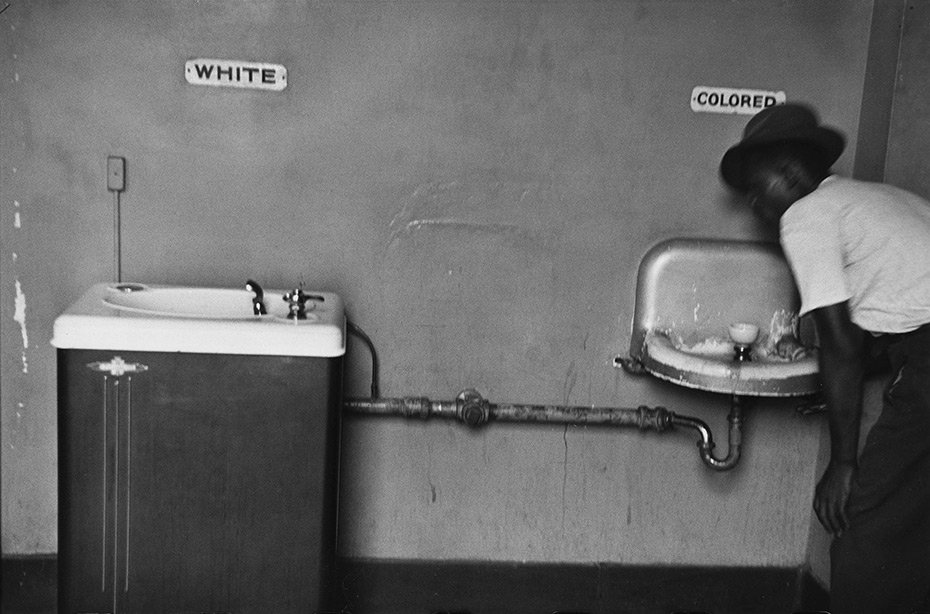

While in New York, Erwitt met Edward Steichen, Robert Capa and Roy Stryker, the former head of the Farm Security Administration. Stryker initially hired Erwitt to work for the Standard Oil Company, where he was building up a photographic library for the company, and subsequently commissioned him to undertake a project documenting the city of Pittsburgh.

While in New York, Erwitt met Edward Steichen, Robert Capa and Roy Stryker, the former head of the Farm Security Administration. Stryker initially hired Erwitt to work for the Standard Oil Company, where he was building up a photographic library for the company, and subsequently commissioned him to undertake a project documenting the city of Pittsburgh.

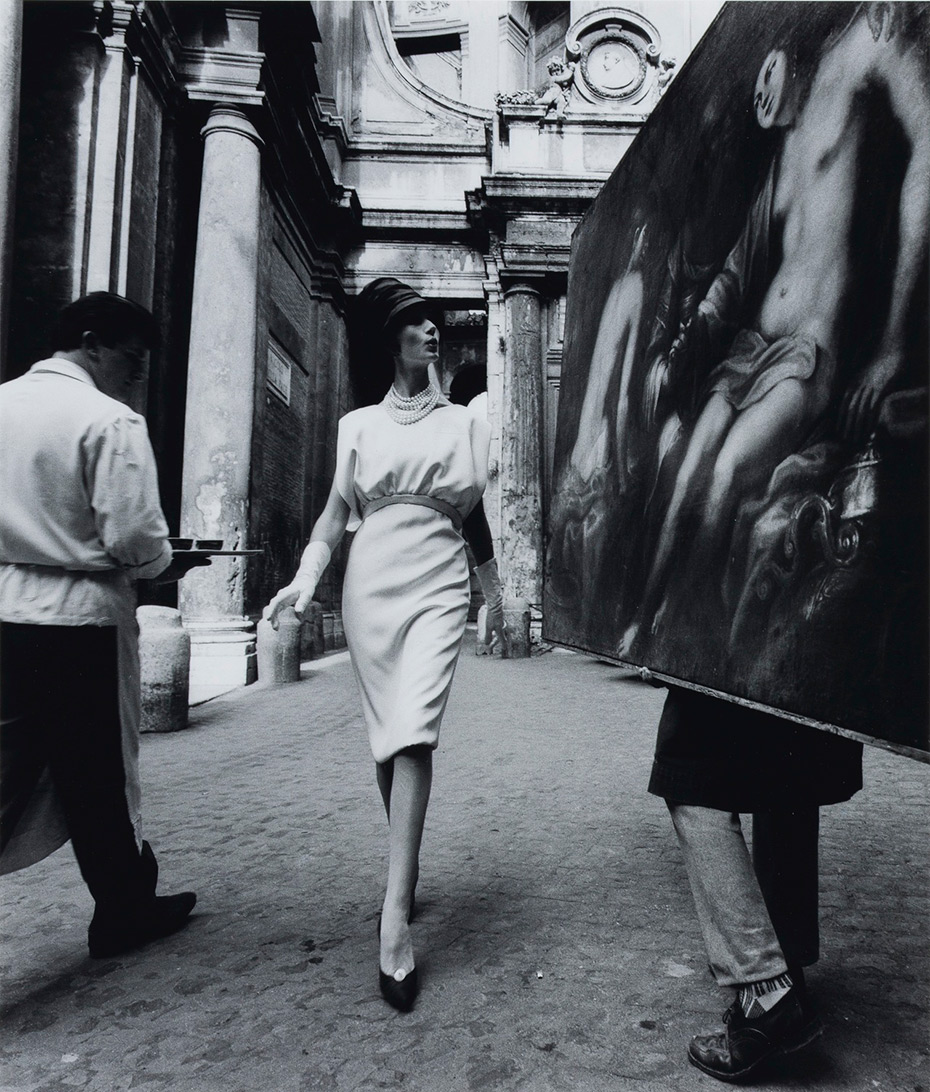

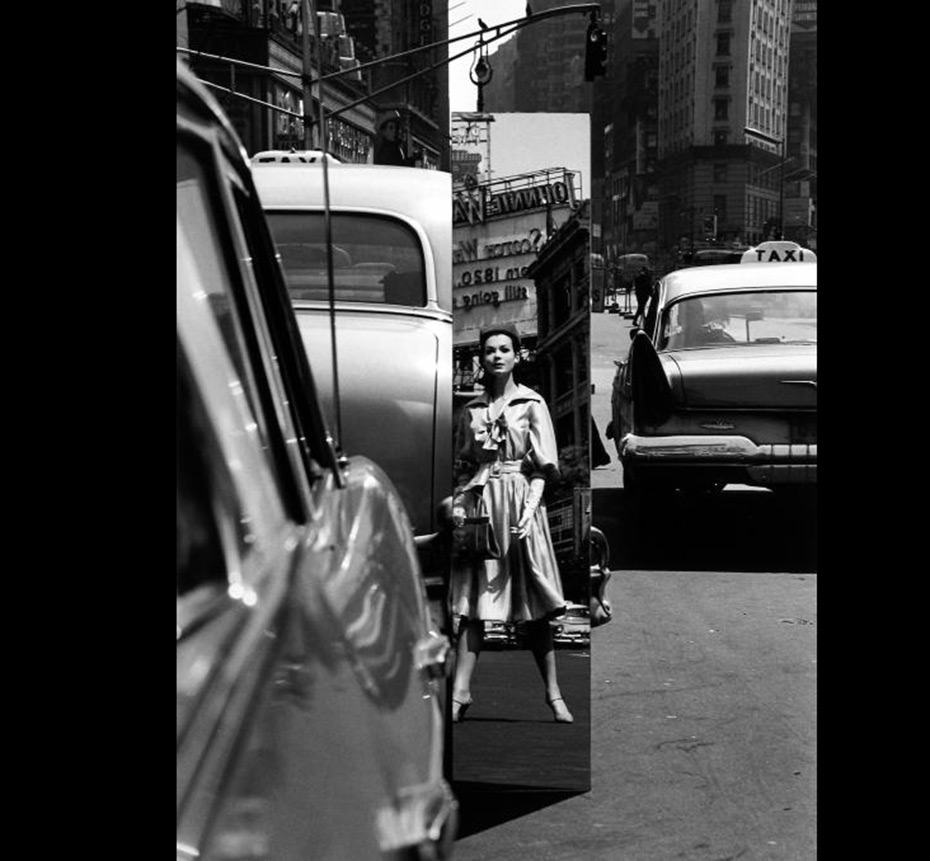

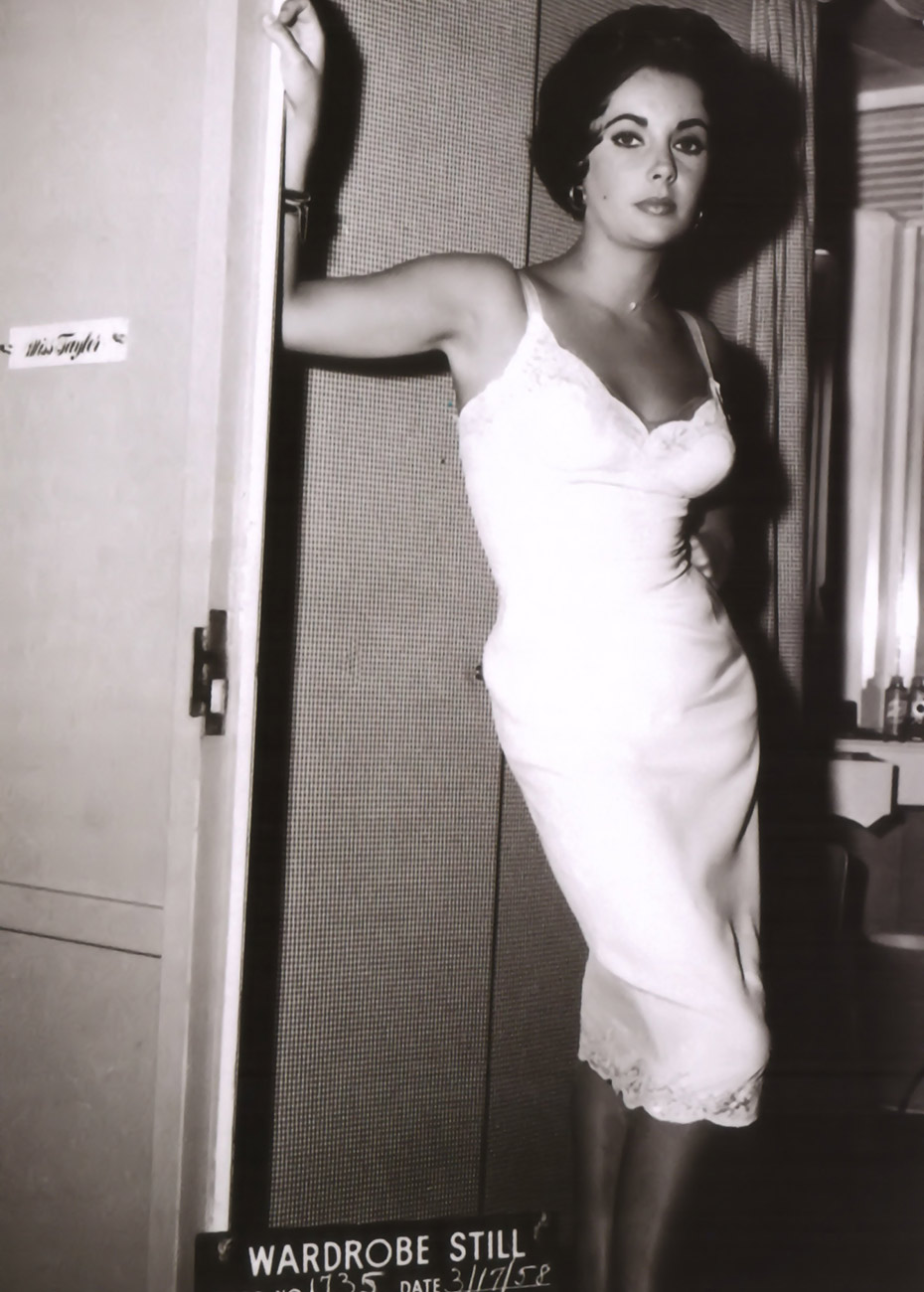

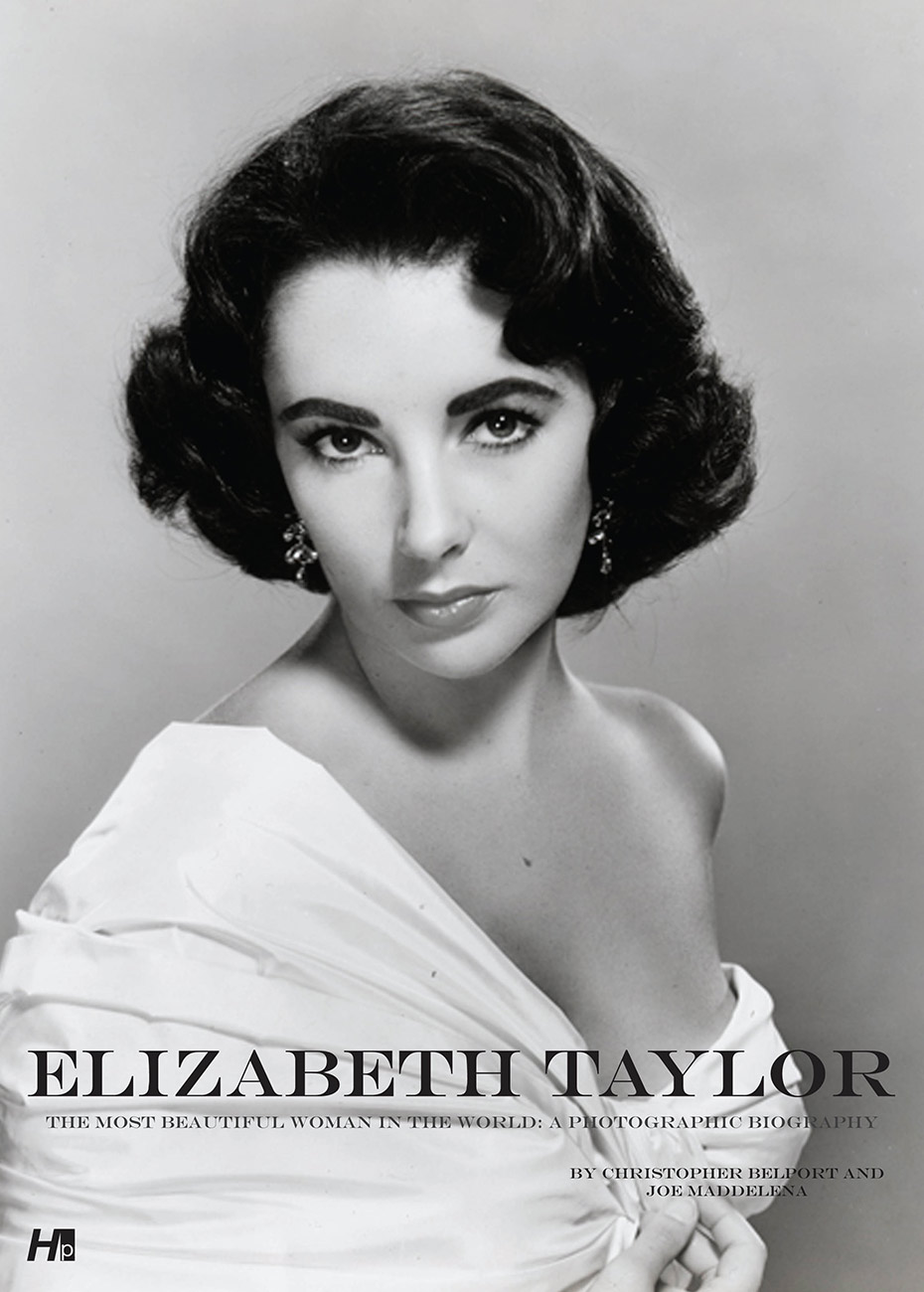

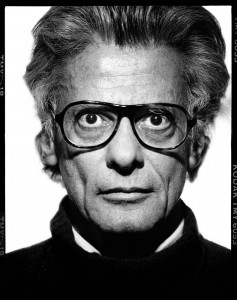

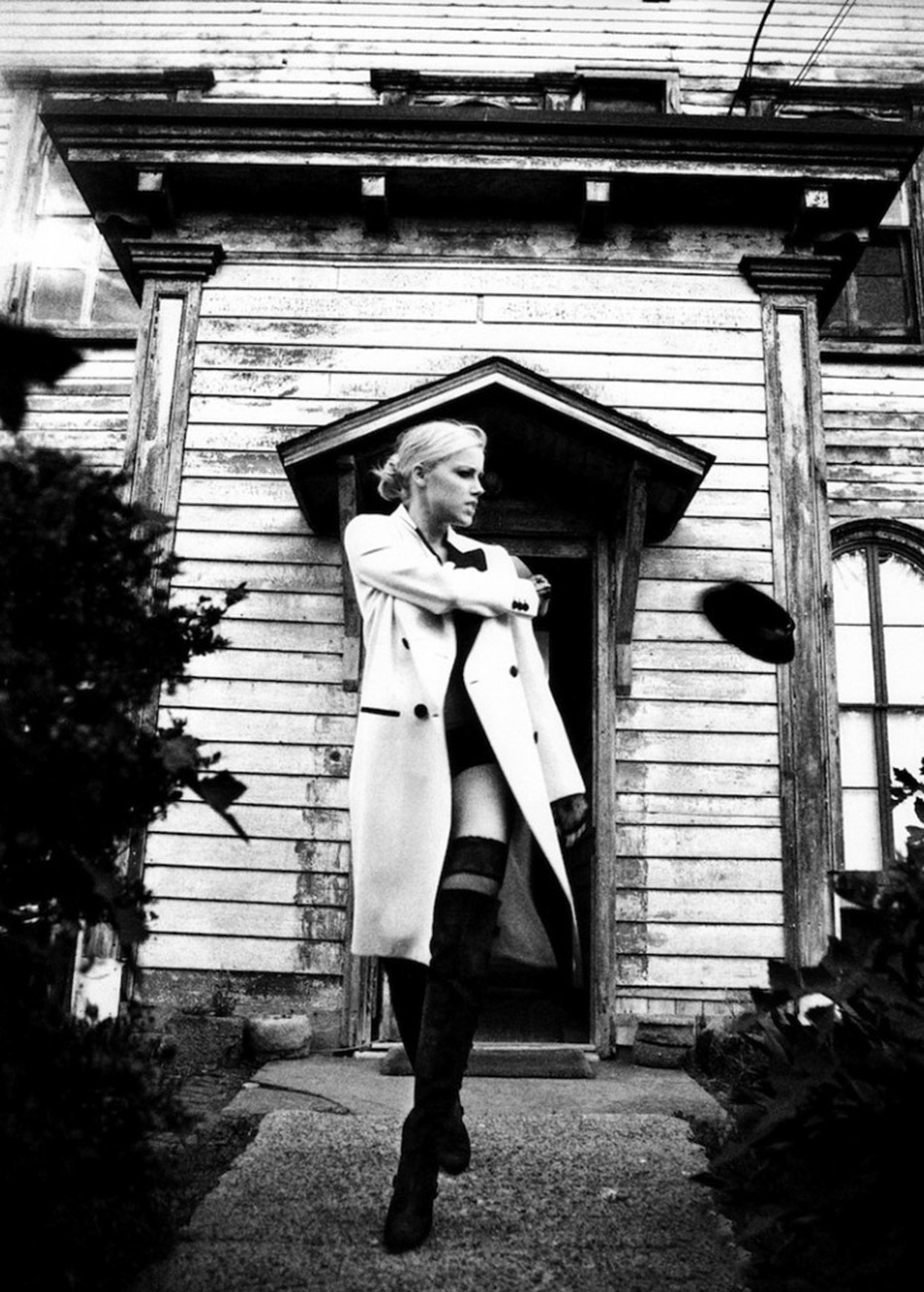

Avedon joined the armed forces in 1942 during World War II, serving as Photographer’s Mate Second Class in the Merchant Marine. Making identification portraits of the crewmen with his Rolleiflex twin lens camera—a gift from his father—Avedon advanced his technical knowledge of the medium and began to develop a dynamic style. After two years of service he left the Merchant Marine to work as a photographer, making fashion images and studying with art director Alexey Brodovitch at the Design Laboratory of the New School for Social Research.

Avedon joined the armed forces in 1942 during World War II, serving as Photographer’s Mate Second Class in the Merchant Marine. Making identification portraits of the crewmen with his Rolleiflex twin lens camera—a gift from his father—Avedon advanced his technical knowledge of the medium and began to develop a dynamic style. After two years of service he left the Merchant Marine to work as a photographer, making fashion images and studying with art director Alexey Brodovitch at the Design Laboratory of the New School for Social Research.

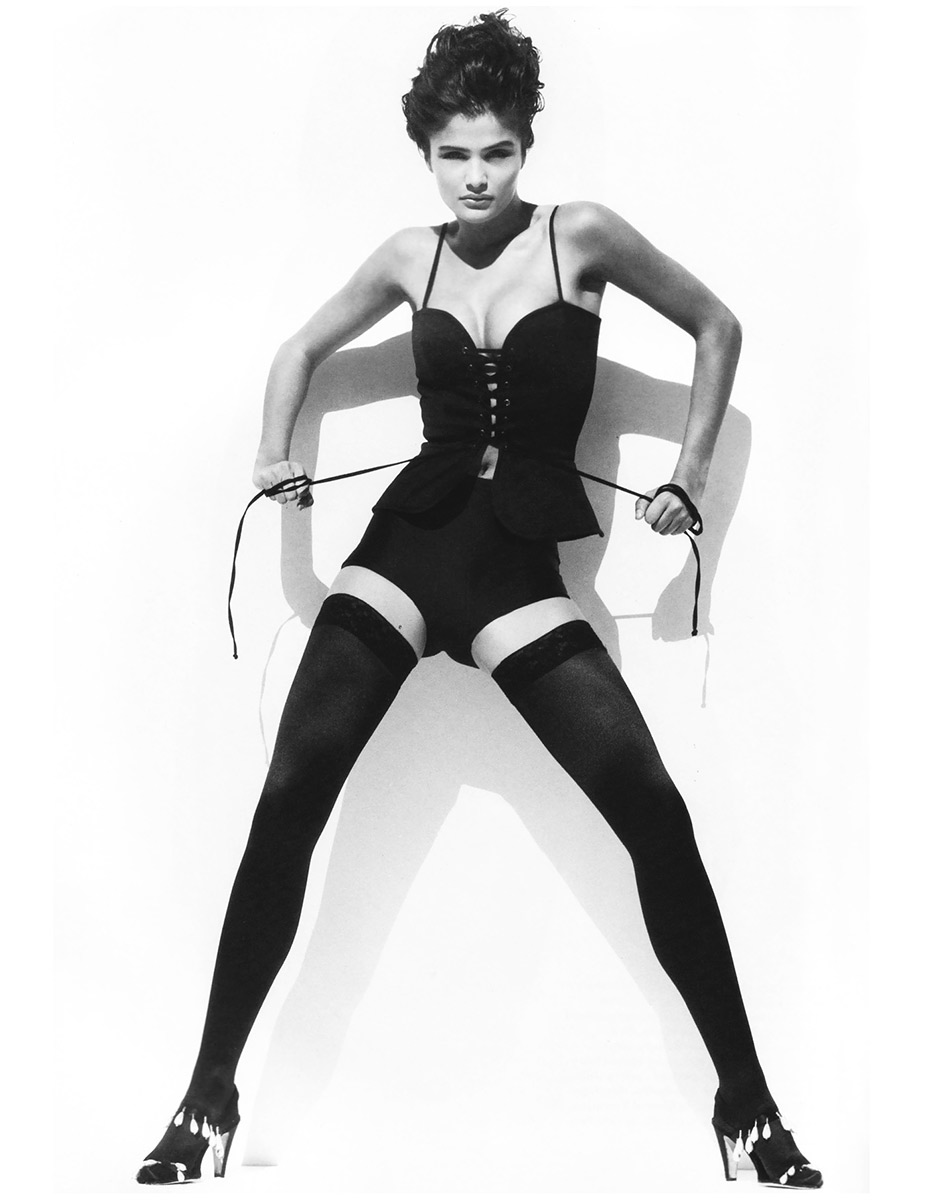

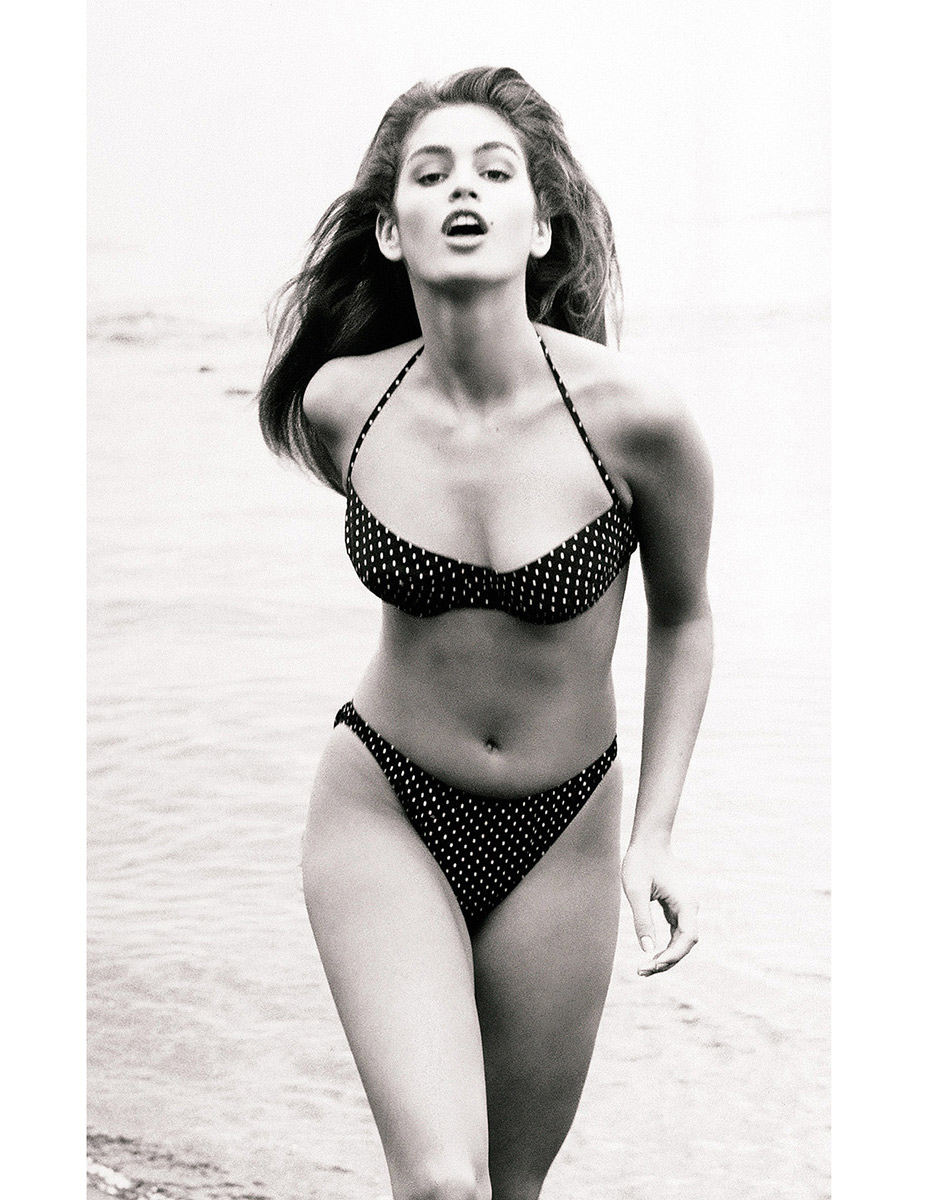

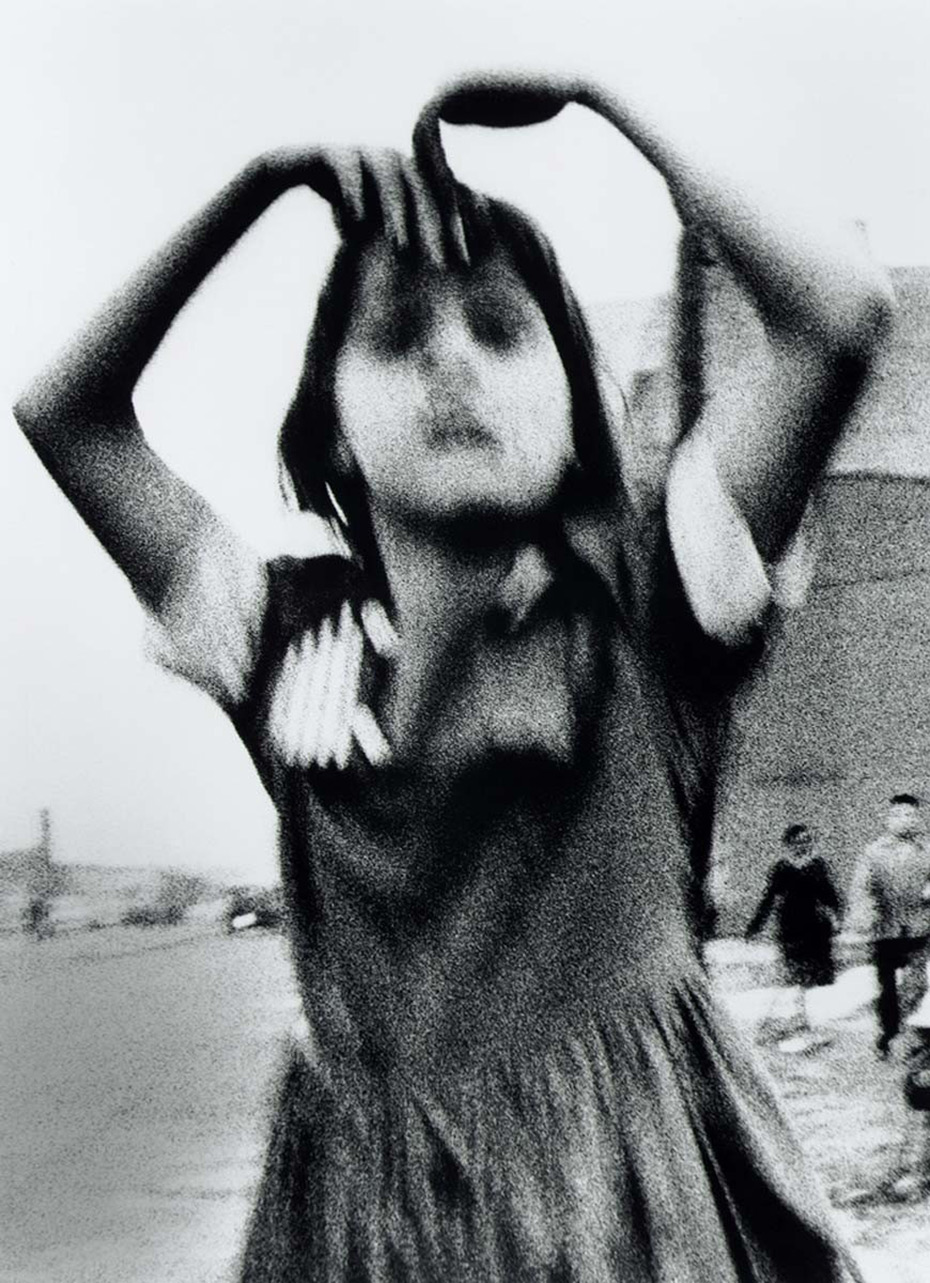

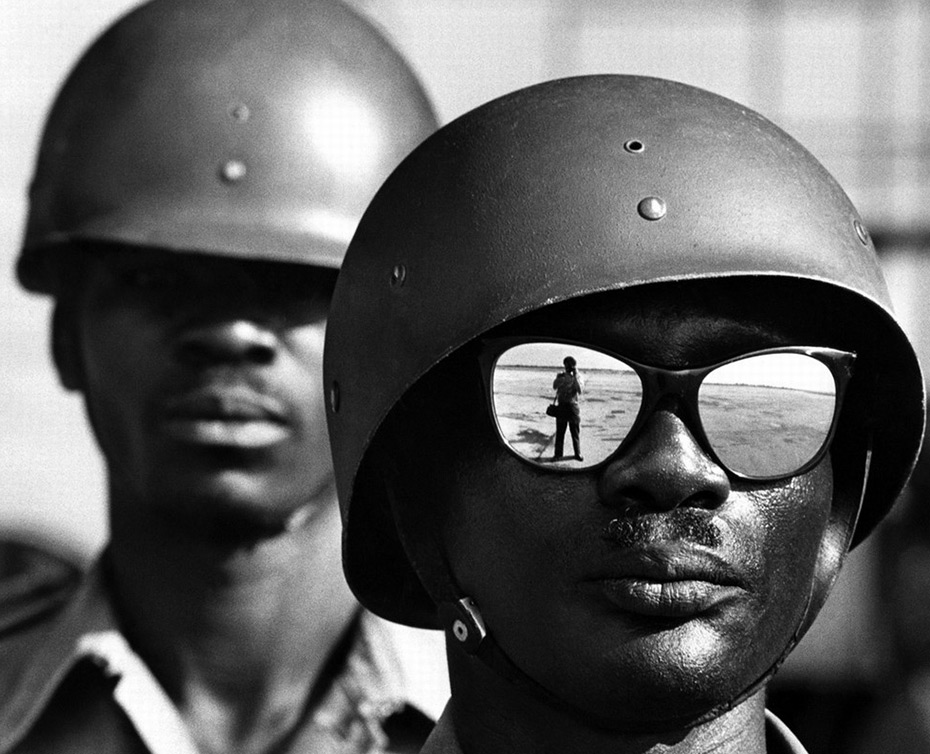

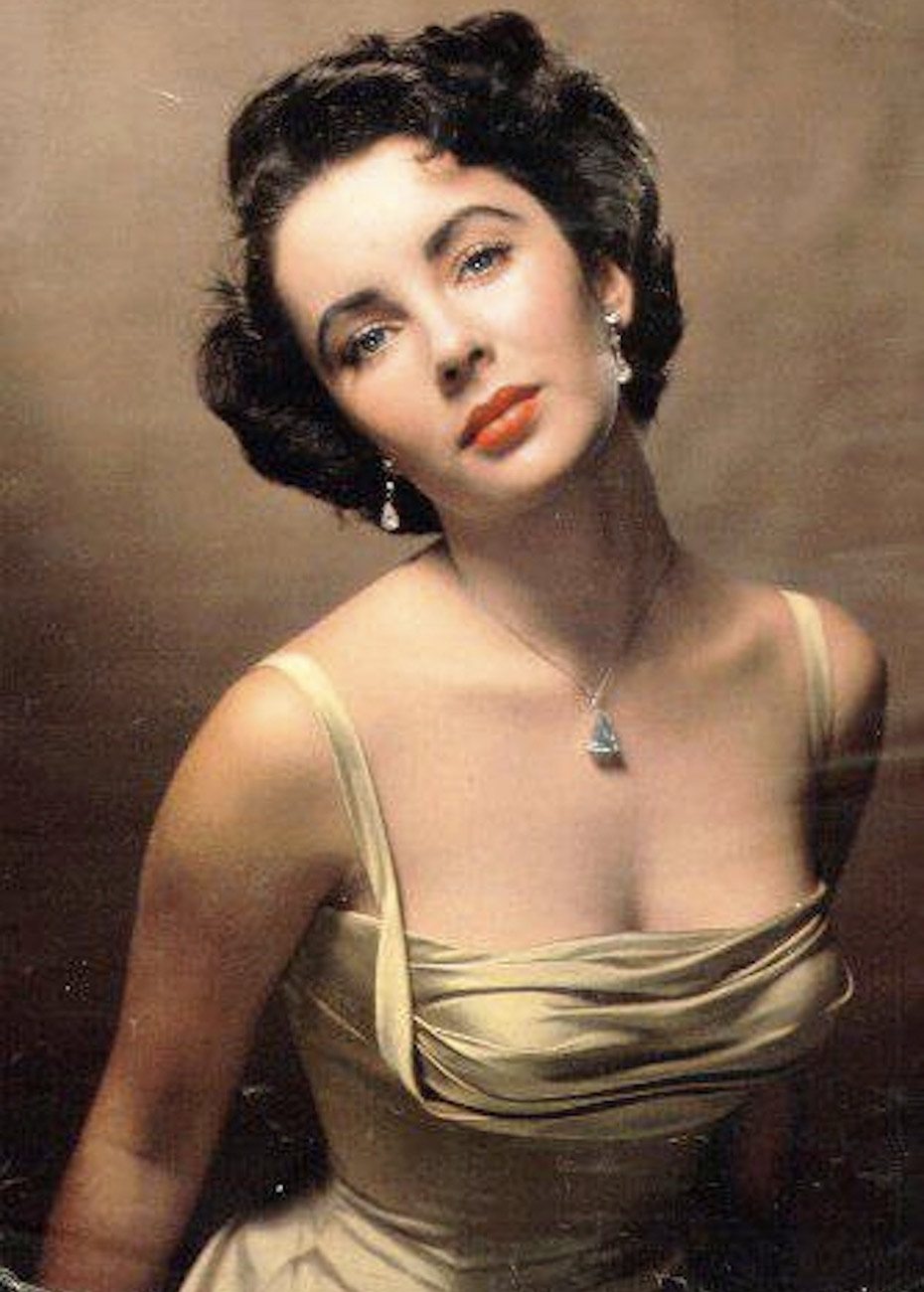

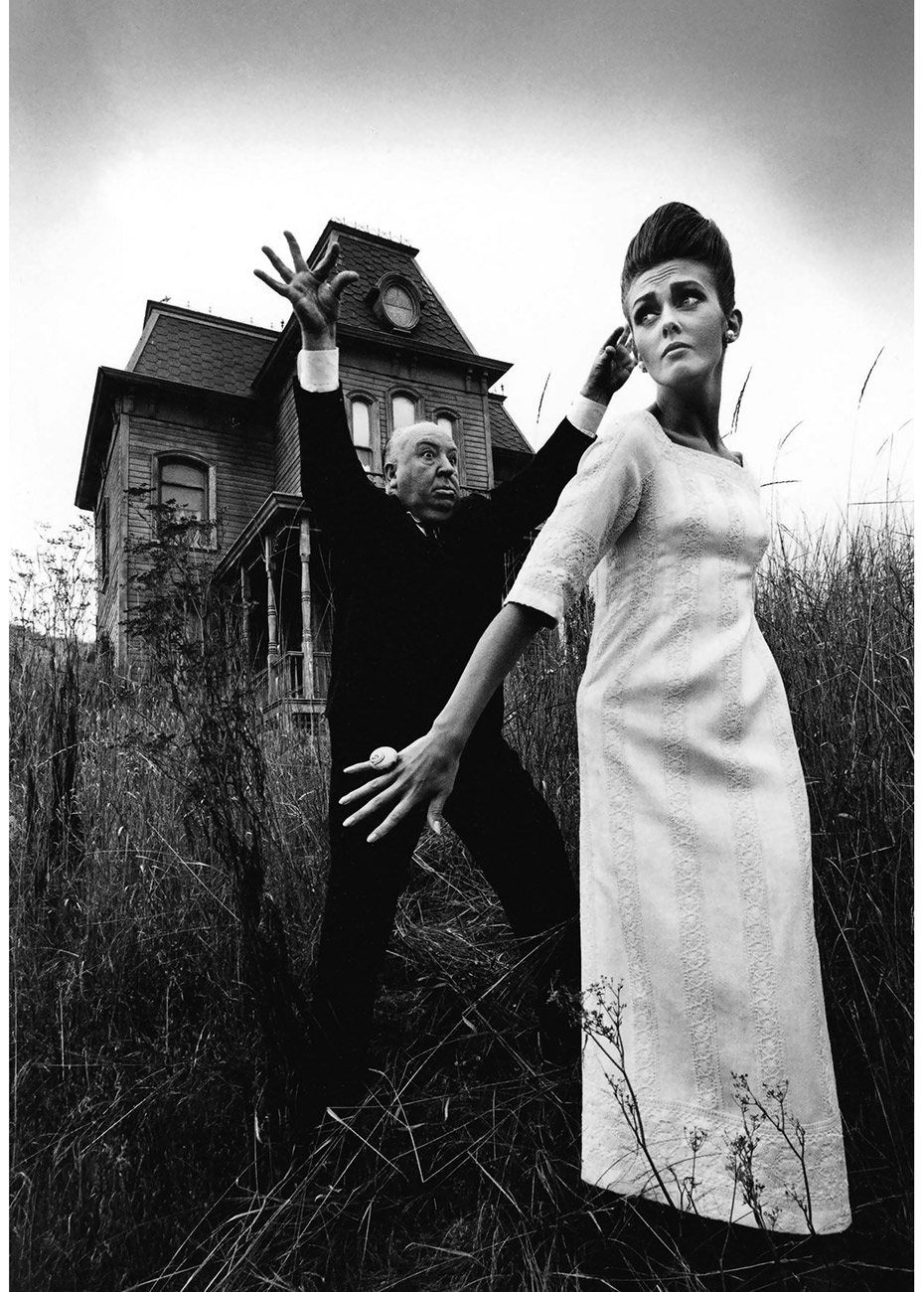

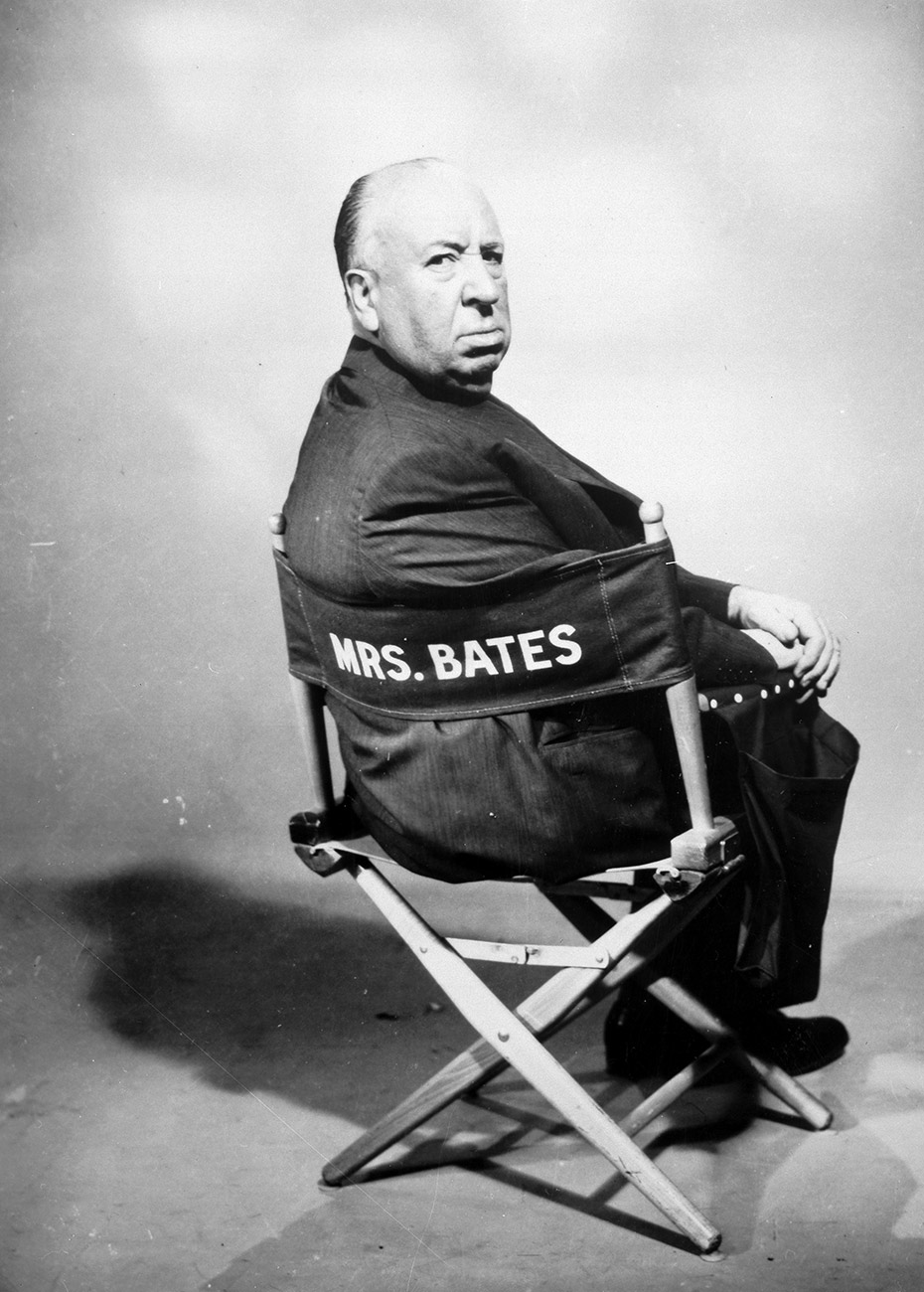

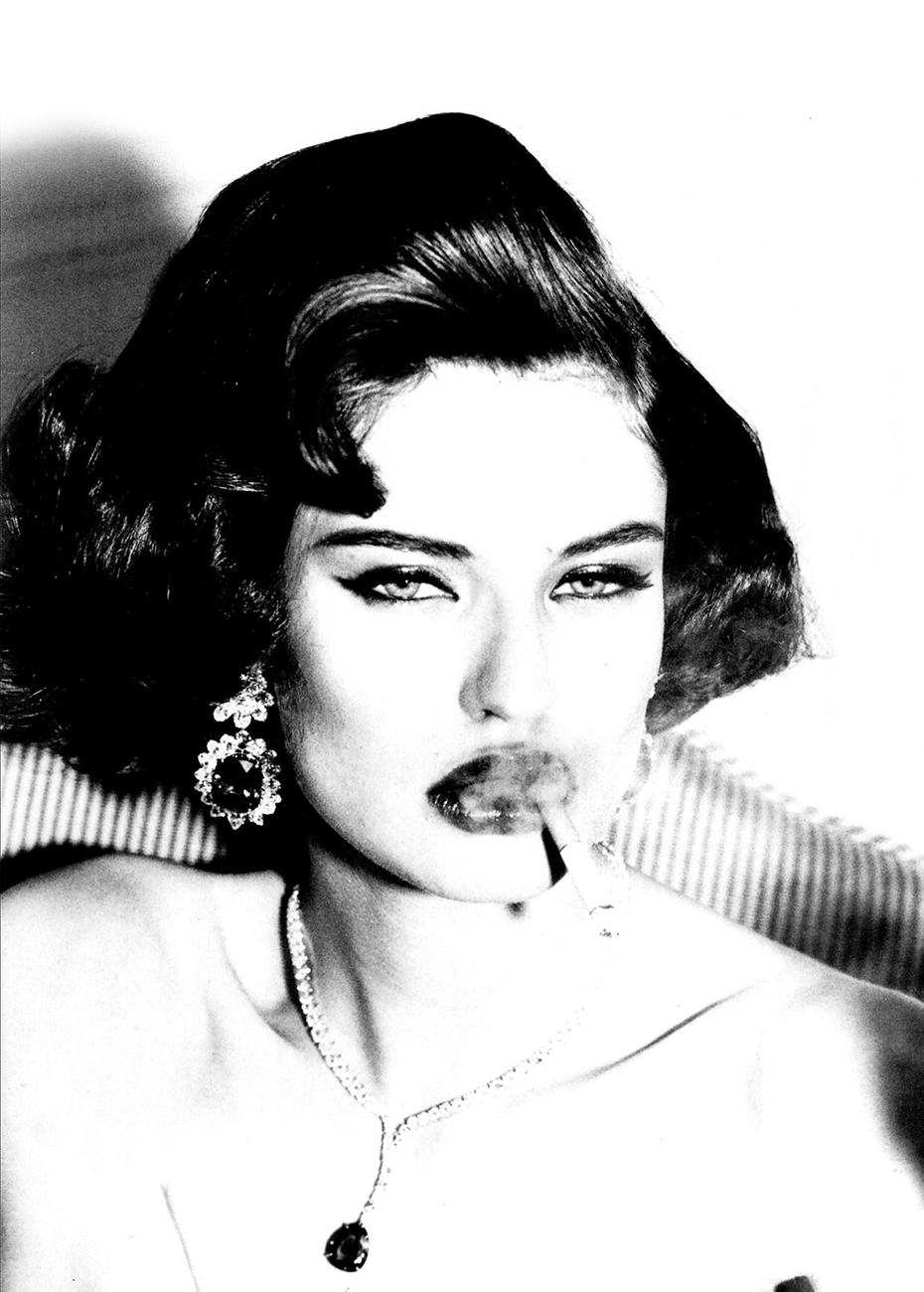

In his life and work, Herb Ritts was drawn to clean lines and strong forms. This graphic simplicity allowed his images to be read and felt instantaneously. They often challenged conventional notions of gender or race. Social history and fantasy were both captured and created by his memorable photographs of noted individuals in film, fashion, music, politics and society.

In his life and work, Herb Ritts was drawn to clean lines and strong forms. This graphic simplicity allowed his images to be read and felt instantaneously. They often challenged conventional notions of gender or race. Social history and fantasy were both captured and created by his memorable photographs of noted individuals in film, fashion, music, politics and society.